Making Water Quality a National Priority

Concern about the quality of water has been present for decades, encompassing concern for both environmental preservation and safe drinking water. The latter is meant to be a public good, meaning it should not be excludable to certain parts of the population, and its use should not be disrupted by another's actions.

Pure public goods have two defining features: ‘non‐rivalry,’ meaning one's consumption of a good does not mean that someone else cannot enjoy the same good, and ‘non‐excludability,’ meaning no one may be prevented from enjoying the good. Water quality is an important environmental example of a public good, since one's consumption of clean water should not reduce water quality for others, and people should not be prevented from consuming the clean water. Along with clean water, many environmental resources are considered public goods, including air quality and a stable climate. However, many question whether environmental resources such as clean water truly meet the definition of 'public goods.' For example, if clean, safe drinking water becomes limited, it becomes both 'rival' in that drinking a glass of clean water may prevent others from accessing it, and 'excludable' in that after it is consumed, it becomes unavailable to others.

In the water pollution episode of the U-M School of Natural Resources "Ecology: Man and the Environment" series (1970), Professor Justin Leonard explains that "man must learn to live in mutualism with nature" and so "our water can be used no longer as a common dump." For generations, the American public has treated water as if it didn't belong to anybody, resulting in the mindset that nobody was reponsible for it. Instead, Leonard claims, "we must all be responsible for it." The environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s argued that clean and safe water should be considered, at its core, a public good. The increasing pollutants being dumped in water - water used for drinking, recreation, and wildlife - upset the idea of water exisiting as a non-rival, non-excludable good. The water quality issue became so urgent and large that the federal government had to get involved.

"Fishable, drinkable, swimmable water. It’s that simple. The law of the land in the US is that all water should be fishable, drinkable, swimmable. And when you think about it, that's what the activists were calling for. You look at the great lakes, and people want to be able to go to a beach, you want to be able to drink the water, you want to be able to eat the fish.”

- Mike Shriberg, Regional Executive Director for the National Wildlife Federation's Great Lakes Regional Center (2017 interview)

In "Who Governs Nature," another episode in the 1970 "Man and the Environment" series produced by the U-M School of Natural Resources, Professor Leonard discusses the increasing urgency of the environmental disasters plaguing the United States at the time of the ENACT Teach-In and the first Earth Day. The water quality crisis included the toxicity of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, and the lack of safe drinking water and general ecological imbalance of the Great Lakes.

In modern American history, the federal government's role in protecting water quality has steadily increased since the 1930s, as has the balance between the conservation approach of developing water resources for economic growth and a greater environmental sensibility about the role of water as a public good and as essential to ecological health. This section examines the gradual emergence of the water quality crisis across the administrations of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945), Harry S. Truman (1945-1953), Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961), John F. Kennedy (1961-1963), Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969), and Richard Nixon (1969-1974). Via water-related disasters, increasing public attention, shifts in attitudes, passage of laws, and utilization of urgency rhetoric, the United States saw a shift from state and local to national governmental regulation.

1930s

Throughout the nineteenth century, state and local governments provided practically all government services for citizens, including defining and enforcing rights, and constructing infrastructure, such as maintaining roads, streets, sewage systems, water-supply systems, and most other infrastructure. The average American citizen had little to no contact with the federal government, whose policies and actions affected most people only indirectly. This was the norm until Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency in the wake of the Great Depression, which caused citizens to look to the federal government to save the day. In the 1930s, Roosevelt established a group of government-sponsored policies and programs called the “New Deal.” The New Deal expanded the federal government's authority, resulted in the government becoming more deeply involved in the lives of the American people. Before the New Deal, the bureaucracy of the federal government was far less developed, but President Roosevelt understood the government's role as one to provide “relief, recovery, and reform” to the nation's failing economy, since years and presidencies of governmental non-intervention clearly had not done wonders for the United States’ economic well-being. Through hydroelectric dams, for example, Roosevelt's New Deal promoted agricultural and urban development and symbolized the conservation philosophy of managing natural resources to increase economic growth.

The 1930s also brought increased attention to the problems of water pollution and generated calls for a stronger response from the national government. This 1937 article in the Michigan Daily, "Stream Life Must Be Preserved," reported on the findings of zoologists who found severe damage to marine life because of industrial pollution of rivers and lakes. The researchers argued that the government must get involved in safeguarding animal life from the destruction caused by water pollution, but at this time most water quality investigation and research still took place at the local level.

In 1938, the New York Times reported on the progress being made in the battle against raw sewage dumping into New York rivers. In an attempt to reduce pollution, the Public Works Department aimed to purify the city's waterways by engaging in ten decontamination projects, including building a $4,000,000 water plant in Flushing, a $5,000,000 plant in Bowery Bay, and a $5,800,000 plant in Jamaica. The goal of these projects was of heavy importance; the PWD felt that the projects "symbolize the new public attitude towards pollution, and bring[s] attention to the tremendous progress being made throughout the area to end it." Hopefully, the Times explained, the projects would mark a step towards ending the dumping of untreated sewage, and mitigate residents' tensions about making New York's water fit for the livelihood and recreation of both fish and humans. Specifically, this article represents the traditional idea that technological solutions could solve the expanding environmental problem. It was widely believed that to fix the broken economy during the Great Depression, the United States needed to support industrial growth, and with the expansion of industry comes environmental pollutants as a necessary cost. Since a political consensus called for more economic growth, the next best thing to stopping the pollutants at their source was the after-the-fact idea of cleaning the waters with advanced technology.

In 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt admitted that the typical way of "getting rid" of pollutants by dumping them directly into the public waters had become a real problem requiring a federal solution. The president released "A Recommendation that the Federal Government Aid in the Solution of the Problems of Water Pollution." The address pioneered the idea of treating water quality as a serious public health issue, stating that Congress had recognized the national importance of pollution abatement in streams and lakes, but there was no quick and easy solution in sight, given the degree of financial, technical, and administrative challenges at present. Roosevelt thus called for the creation of a Divsion of Water Pollution Control in the United States Public Health Service and for the establishment of a permanent system of federal grants and loans to asssist in constructing pollution abatement projects. This new federal process allocated approximately 2 bilion dollars over the next two decades to construct municipal works necessary to abate the ever-growing water pollution problem.

The New Deal in the 1930s increased the sense that water pollution represented a national problem and increased concerns about industrial dumping, sewage contamination, and other degredation of streams, rivers, and lakes. However, Roosevelt concluded his 1939 report by stating: "Inasmuch as the needed works are chiefly treatment plants for municipal sewage and industrial waste, the responsibility for them rests primarily with the municipal government and private industry." In other words, although Roosevelt did declare water pollution to be an issue that needed much attention, and although Congress agreed to provide federal support through implementing public works actions, water pollution remained primarily a local issue to be addressed with private solutions.

1950s

Beginning in 1868, the Cuyahoga River caught fire thirteen times over the next century due to a build-up of oily debris. Cleveland, Ohio, which served as an industrial hub in the 1950s, was home to railway, steel and transportation manufacturers that contributed to the relentless disposal of waste and sewage into the river. The lack of waste disposal management and continued production in Cleveland resulted in the Cuyahoga River becoming one of the most polluted rivers in the United States, which caused the Cuyahoga River fire of 1952, pictured to the right. Train sparks ignited the oil residue in the river, yielding flames that engulfed ships and factories, and causing roughly $1.5 million in damage. According to some accounts, many Cleveland residents and especially city officials were not troubled about water pollution and the sequential river fires, viewing destruction as "a necessary consequence of the industry that had brought prosperity to the city."

Events such as the Cuyahoga River fire resulted in greater public attention to the problems of water pollution and conservation. In 1953, just before leaving office, President Harry S. Truman issued a "Special Message to the Congress on the Nation's Land and Water Resources." Truman called to the attention of the Congress several recent actions designed to provide a better basis for the development of our water and related land resources. "These resources are a foundation," he declared, "upon which rest our national security, our ability to maintain a democratic society, and our leadership in the free world. All too frequently their significance has been obscured among the dramatic events which have characterized our time."

In realizing the importance of properly planned water resource development, Truman appointed the Resources Policy Commission, a special commission created in 1950 to maintain a consistent national policy for water conservation and use development. The Commission harnessed the cooperative effort of Americans, and clarified the complex problems of water-resource planning by providing analysis of water management. Truman made the report a public document, and supplemented it with specific field studies of resource development in major affected regions to draw up a background of great accomplishment and relay vigorous action to protect the public welfare in river basin development. Still, however, Truman's goal with his address and creation of the Resource Policy Commission was to harness water development and management as a growth strategy. He believed that the job of getting our land and water developed, was so big that we must enlist the participation of all agencies-- federal, state, community, & private enterprise. Finally, although Truman concluded that federal funds would be the final answer to the water pollution issue, he expressed slight ideas of the presidents before him, explaining that the results can be seen quickly and completed efficiently only if States and communities invest their dollars.

"The Government should continue to encourage more local and State responsibility. This does not mean promising the States or communities something for nothing--far from it. Administration by the States of Federally provided dollars alone is not real responsibility. Indeed, full reliance on the Federal Treasury is in anything but the best interest of the community, the State, and the Nation."

- President Harry S. Truman, 1950

Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, who succeeded Truman, called for better water quality but did not support a strong role for the federal government in enforcement against pollution. In 1954, Eisenhower signed a conservation bill passed by Congress that amended the Water Facilities Act. The measure emphasized federal loans and technical assistance to allow private interests, especially farms and ranches, to better manage the water supply through flood control and watershed improvements. Eisenhower praises the measure to "conserve the vital water and soil resources of the United States" and called for teamwork between private and public actors and local, state, and federal governments.

Six years later, in 1960, President Eisenhower vetoed an amendment to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act on the grounds that "water pollution is a uniquely local blight." The congressional law would have increased federal grants to municipalities for construction of sewage treatment works from $50 million to $90 million per year over the next decade. Eisenhower called rivers and streams a "priceless national asset" and admitted that water pollution threatened public health, but he argued that state and local governments were primarily responsible for addressing the problem and that the federal role should be minimal. This stance helped lead to the environmental crisis of the 1960s as industrial contamination, agricultural pesticides, and sewage overflow increasingly contaminated rivers and lakes across the nation.

"Because water pollution is a uniquely local blight, primary responsibility for solving the problem lies not with the Federal Government but rather must be assumed and exercised, as it has been, by State and local governments... This Administration from the beginning has strongly supported a sound Federal water pollution control program. It has always insisted, however, that the principal responsibility for protecting the quality of our waters must be exercised where it naturally reposes -- at the local level."

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1960

1960s

The decade of the 1960s brought growing public unease over environmental pollution, and liberal Democratic administrations in Washington proved much more willing to support federal solutions. Soon after taking office, President John F. Kennedy signed the Water Pollution Control Act that Eisenhower had vetoed, and he labeled conservation of resources a national priority. His successor Lyndon Johnson provided an even stronger federal response to the issues of environmental degradation as grassroots organizations and residents of large metropolitan areas began to express concern about the destructive consequences of industrialization and rapid development. In 1963, Johnson signed Clean Air Act, a law designed to control pollution on a national level by regulating various types of emissions, but enforcement remained weak until enhanced legislation in the 1970s.

Johnson addressed pollution directly in a "Special Message to the Congress on the Nation's Health" in 1964. In this important address, LBJ explicitly gave the federal government primary responsibility for preventing further damage to the natural environment. He discussed air pollution from factories and pesticides from industrial sources and warned that "the pure water we once took for granted is being polluted by chemicals and foreign substances." President Johnson called for "effective safeguards to protect our people from hazards in the air we breathe, th water we drink, and the food we eat." But many environmental activists believed that the Johnson administration did not go far enough in supporting technological fixes rather than seeking stricter regulations on industry, the main contributor to water pollution. Lyndon Johnson played a key role in making environmental quality more of a federal problem but failed to challenge industrial development and continued to prioritize economic growth.

Needed: Clean Water

The Federal Water Pollution Control Administration, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior, released a booklet in 1964 titled "Needed: Clean Water. Problems of Pollution." The national publication booklet provided facts and statistics for the US public, motivating them to educate themselves and take action with their local governments.

The booklet maintains that water is essential for everything that lives on Earth. However, as the annual amount of rain stayed the same and the population grew, Americans faced the possibility of a water shortage. In 1964, it was estimated that 335 billion gallons are used per today, with that number expected to grow to 600 billion gallons used per day by 1980. More people were using more water than ever before – for bathrooms, garbage disposals, laundry, lawn sprinklers, industry and agriculture. However, water could be reused safely via water treatment plants where used water could be treated, filtered and chlorinated so it was safe for drinking. A water conservation program would also help make water more available – such as building more dams, preserving vegetation and forest cover, preventing erosion and enforcing better practices by cities, industries and farms. Sewage treatment plans capable of primary and secondary treatment of water would be the best way to treat used water effectively and safely. Unfortunately, even with the improvement of treatment systems, in the 1960s, water pollution of American rivers was six times greater than in 1900 and contained acid mine drainage, viruses, pesticides and industrial wastes.

The problem of water pollution moved to the center of the agenda at federal, state and local government levels in the mid-1960s. The federal government, more than ever before, provided money to build waste treatment plants, conducted research to find better ways to enhance water quality, enforced federal laws against pollution, and created pollution control programs. State agencies set water quality standards, assessed and analyzed pollution within the state, and checked the operation of sewage plans. Locally, communities faced mandates to insure that new building developments had proper sewer systems with secondary treatment capability, plan for new plants as population increased, and train employees that could maintain the plants.

The Water Quality Act of 1965

In October 1965, Lyndon Johnson signed the Water Quality Act, authored by Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, to develop federal water quality standards for interstate watersheds and waterways. This law fully recognized that water pollution represented a national problem and established standards across state boundaries, thus introducting federal regulatory measures in the absence of state action. The Water Quality Act doubled annual federal construction grants to $150 million, facilitated multi-community and large construction programs, reorganized responsibility within federal administrations, and established clear, innovative water quality violation standards. At the signing ceremony, President Johnson proclaimed that "the hour is late; the damage is large. The clear, fresh waters that were our national heritage have become dumping grounds for garbage and filth. They poison our fish; they breed disease; they despoil our landscapes." Johnson also directly criticized industry in much stronger language than ever before, attacking chemical companies, oil refineries, and factories for turning rivers that belonged to the public interest into "sewers" and "pipelines for toxic wastes." The president specifically lamented the The main provisions of the Water Control Act of 1965 include:

The U-M School of Natural Resources addressed the importance of the Water Quality Act of 1965 in its production "Who Governs Nature," part of the "Ecology: Man and the Environment" series televised in 1970. In this excerpt, Tony Abar of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources explains how the federal law transformed water quality control by incentivizing state governments to make pollution a priority and participate in regional compacts on interstate waterways. "With this impetus, and eventually the groundswell of public concern," Abar observed, "the states have been getting into the water quality control in a big way in recent years."

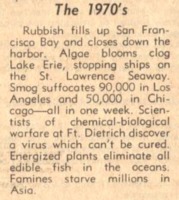

1970s

"I think that 1970 will be known as the year of the beginning, in which we really began to move on the problems of clean air and clean water and open spaces for the future generations of America."- President Richard Nixon, 1970

In the late 1960s, the massive oil spill off the Santa Barbara coast, the catching on fire of the Cuyahoga River, and the proclaimed death of Lake Erie created a sense of environmenal crisis and a widespread belief that the federal govrnment had to do even more--that existing policies were not nearly nough. Things seemed to be getting worse, not better. Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act, inspired by a decade of environmental destruction and ruin. In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the NEPA legislation and established the Environmental Protection Agency to coordinate federal policy by managing environmental risks and enforces regulations regarding environmental quality. Later that year, Nixon signed the Clean Air Act of 1970, but he then proved unwilling to support the Clean Water Act of 1972.

In 1972, the U.S. Congress passed the landmark Clean Water Act, which the EPA backed and which validated the work of environmental activists and organizations that were demanding federal action. The Clean Water Act pledged to "restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's waters"--including eliminating the discharge of all toxic pollutants by 1985, making all navigable waters safe for animal life and human recreation, charging the EPA with primary responsility for enforcement, and providing billions of dollars to state and local governments to ensure compliance. On October 17, President Nixon vetoed the legislation as too expensive for American taxpayers, saying that its "laudable intent" could not justify the "unconscionable" and "budget-wrecking" total cost of $24 billion. In doing so, Nixon ignored the recommendation of his own EPA director William Ruckelhaus, who warned that the White House would be attacked for "having initiated a highly publicized and initially controversial program which ended up in total failure." During the two years of congressional debate on the clean water legislation, the White House had endorsed the idea of the law but also supported the opposition of industry to many of its specific provisions, especially the mandate to ban all pollutant discharges by 1985. Nixon instead called for a more limited program that would provide $6 billion for states and localities to upgrade sewage treatment plants, without the total prohibition on industrial effluents.

In late October, the U.S. Congress overrode Nixon's veto by large margins and enacted the Clean Water Act of 1972 into law. The Senate vote was 52 to 12, with most members of both parties ignoring the president's arguments about the excessive cost. Environmental activists argued that the taxpayer argument was a smokescreen and that the veto had revealed Nixon's true politics and real interests in defending the polluting corporations that donated money to the Republican party. Many critics charged that Nixon had only jumped on the environmental bandwagon because of his sense that public opinion demanded it, and in recognition of the groundswell of activism that culminated in Earth Day. Environmental Action, which strongly criticized the Nixon administration throughout the water quality debate, proposed that his veto really resulted from "dissatisfaction with the very stringent requirements for water pollution control which Congress imposed on industrial polluters." Richard Nixon was simply hypocritical, editor Peter Harnik of Environmental Action wrote in another assessment: "He is too closely aligned with American business" to supportmeaningful pollution controls. "He says 'environment' while he thinks 'profits.'"

The Clean Water Act of 1972 had a major positive impact on water quality and anti-pollution regulations in the United States. Through various routes, pathways and partnerships, federal funding became available to state and local governments to aid the clean up of American waterways. For example, since the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District has invested roughly $3.5 billion towards river purification, including the development of new and improved sewer systems, and is projected to endow over $5 billion over the next thirty years to maintain the wastewater system. The Clean Water Act of 1972 motivated activists to clean up their communities; in Cleveland, this included politicians, employees of Cleveland City Utilities, members of the Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization, owners of local supply companies, and other local activists.

The water pollution problems in places such as Santa Barbara and Cleveland, combined with the activism of the Earth Day era, helped transform environmental protection from a local and state into a federal issue. The Clean Water Act of 1972, for the first time, established nationwide standards for industrial discharge of wastewater, abandoning the approach that left regulation to state and local governments in order to determine water quality. The Clean Water Act highlighted how large industries and factories were the main contributors to the "environmental crisis" and made regulation of hazardous pollutants a federal responsibility.

Sources:

U-M School of Natural Resources/University of Michigan Television Center, "Ecology: Man and the Environment," Part 8: "Water Pollution," 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

U-M School of Natural Resources/University of Michigan Television Center, "Ecology: Man and the Environment," Part 11: "Who Governs Nature," 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Bentley Image Bank, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Public Papers of the Presidents, 1939, 1953, 1954, 1960, 1964, 1965, 1970, 1972

Public Law 92-500, "An Act to Amend the Federal Water Pollution Control Act," October 18, 1972

Peter Harnik, "Nixon's the One. (The Environment's the Other)," Environmental Action, September 30, 1972, 3-5

EPA, "Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA)," October 13, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/glwqa

"About the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement," Binational.net, https://binational.net/glwqa-aqegl/

"2015 Stress in America." Accessed December 12, 2017. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2015/snapshot.aspx

Russell McLendon, "The Clean Water Act turns 40," MNN - Mother Nature Network. December 13, 2017, https://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/wilderness-resources/blogs/the-clean-water-act-turns-40

Clean Water Action, "Michigan," 2017, https://www.cleanwateraction.org/states/michigan

"What are public goods?" Khan Academy, 2017, https://www.khanacademy.org/economics-finance-domain/microeconomics/consumer-producer-surplus/externalities-topic/a/public-goods-cnx

Marshall Sprague, "POLLUTION REDUCED: Progress Made in Battle to End Pouring of Raw Sewage Into New York Waters Old Method of Disposal DRIVE SPEEDS UP ON POLLUTION Jamaica Bay Plans Recreational Waters," New York Times, December 25, 1938

"Water Pollution vs. Water Supply." The Christian Science Monitor, August 14, 1956

Michael Rotman, "Cuyahoga River Fire," Cleveland Historical, September 22, 2010, https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/63

Environmental Protection Agency, "Water Topics, September 11, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/environmental-topics/water-topics

Michael Scott, "Cuyahoga River fire 40 years ago ignited an ongoing cleanup campaign," Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 22, 2009

Environmental Protection Agency, "Summary of the Clean Air Act," August 24, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-air-act.

Matthew Kotchen, "Public Goods," December 8, 2012, http://environment.yale.edu/kotchen/pubs/pgchap.pdf

Robert Higgs, "The New Deal and the State and Local Governments," March 01, 2008, https://fee.org/articles/the-new-deal-and-the-state-and-local-governments/

Daniel Estrin, "Clean Water Act 101-A bit of legislative history – Green Law." Green Law — Blog of the Pace Environmental Law Programs, April 1, 2011, https://greenlaw.blogs.pace.edu/2011/04/01/cwa101/

Richard Nixon: "Special Message to the Congress on Environmental Quality," February 10, 1970, American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2757

Richard Nixon: "Veto of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972," October 17, 1972, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=3634

Robin Madel, "Nixon's Clean Water Act Impoundment Power Play." The Huffington Post. March 22, 2012, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/robin-madel/nixons-clean-water-act-im_b_1372740.html

E. W. Kenworthy, "Clean-Water Bill Is Law Despite President's Veto," New York Times, October 19, 1972.

Elsie Carper, "EPA Chief Urges Nixon Sign Water Bill," Washington Post, October 17, 1972.

Richard Nixon: "Remarks on Signing the Clean Air Amendments of 1970," December 31, 1970, American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2874

"Environment." Democratic Outreach and Engagement Taskforce, http://engage.dems.gov/environment/water-quality-act-of-1965-and-air-pollution-control-act/

Environmental Action Newsletters

Michigan Daily Digital Archives