Ecological Politics of ENACT

“Man has so severely despoiled his natural environment that serious concern exists for his survival.”

ENACT was not only a student organization but the face of an environmental movement taking place in both Michigan and the whole United States. As a grassroots effort to educate citizens of the environmental issues and what they could do to help, ENACT created a philosophy of responsibility, education, and action.

In the first newsletter created by ENACT, they direct blame for environmental degradation on to mankind in the very first sentence. ENACT did not shy away from accusing humans of destroying the planet and from the beginning integrated it into their organizational philosophy. To ENACT, man was responsible for the environmental destruction happening across the planet and thus, man should be responsible for fixing the problem. Their philosophy was cultivated over a series of months and what they preached come to fruition at the Teach-In in March of 1970.

ENACT believed “that a great university like [the University of Michigan] should have a major influence on society,” and that is why they worked “to bridge the gap between the campus and the general public.” Using the platform of a major university that had given birth to the Teach-In movement in the 1960s, ENACT waged war against environmental destruction.

“If you are not a part of the solution - then you are a part of the problem”

A major aspect of the clubs philosophy was education and action. In a pamphlet created by ENACT, it stated clearly that the “The goals of ENACT are twofold:

1. To work to increase the level of public concern and awareness of our critical environmental problems.

2. To initiate constructive action programs which will help to preserve and enhance the quality of life on our despoiled planet”

The tactics of ENACT were clear. First, they must educate people and second they must create means to protect and preserve the planet. Hosting a Teach-In was an obvious solution to accomplishing their first goal as well as build momentum for their second goal. Although the Teach-In was their largest event and thousands of people were educated this way on the environment, ENACT also educated members of the community through informational pamphlets containing information on how the average person can implement environmentally friendly practices into their everyday lives.

The Guidelines for Citizen Action on Environmental Problems was one of these pamphlets. Like other ENACT materials, ENACT was not shy when addressing the issues. The pamphlet opened with “the crisis now facing our environment demands immediate effective action by all of us. It is not enough simply to be aware and concerned… we must all act, even if the action is only in our own backyards.” ENACT listed advice on how to limit personal air pollution, decrease water pollution, decrease solid waste, decrease noise pollution, keep the land looking beautiful as well as discouraged the use of pesticides and encouraged fewer children per couple. Although some tips were as easy as “keep your car well tuned” to decrease air pollution, others were as personal as creating a “two-child family...maximum.” The wide range of advice and commitments to the environment advertised in the pamphlet were not a mistake. ENACT wanted everyone to do as much as they could for the environment, even if it just meant “plac[ing] several bricks in the flush tank of every toilet you use.”

By passing out pamphlets and educating others on how to become more environmentally aware, ENACT spread the message that “we all must be willing to make personal commitments and sacrifices to protect the environment” The use of “we” and “us” is continued throughout the pamphlet, reinforcing that environmental issues were not a single person issue, but a world issue. ENACT understand that without public support, the environment would continue to be destroyed, therefore it was important to establish a community of environmentally conscious people. By activating the populous, it also strengthened grassroots efforts, which were the foundation of the environmental movement.

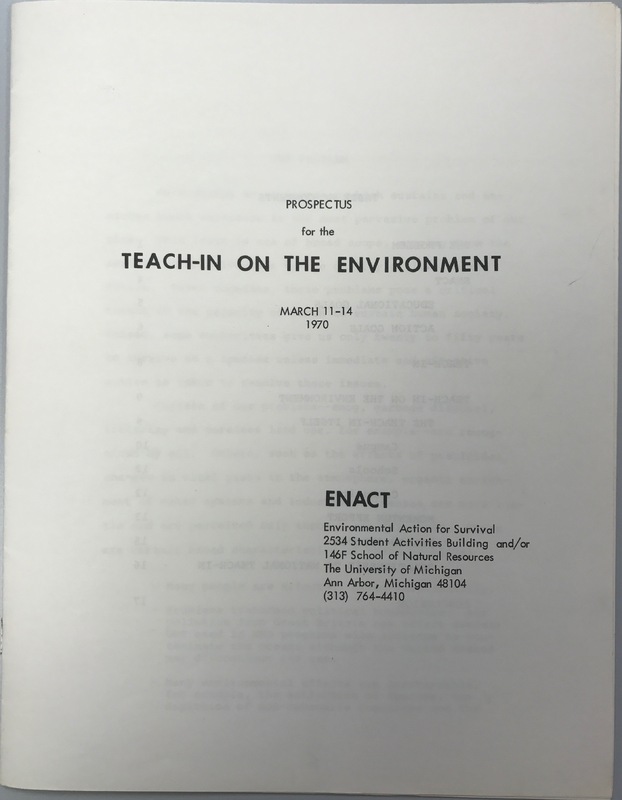

In the Prospectus of ENACT, their philosophy of action was highlighted throughout with heavy emphasis. Like all their teaching and information materials, the environmental crisis was stated, reiterating the importance of understanding the issues. In the prospectus they state,

“Maintaining an environment which sustains and enriches human existence is the most pervasive problem of our time. This issue is one of broad scope, ranging from the aesthetics of wilderness to the quality of life in the cities. Taken together, these problems pose a critical threat to the capacity of Earth to sustain human society. Indeed, some authorities give us only twenty to fifty years to survive as a species unless immediate and effective action is taken to resolve these issues.”

ENACT established how immediate the threat to the environment was in order to emphasize the need for action and through which channels action should go through. The focus on human survival and the fragility of the planet was the only way "will effective action be motivated through the numerous channels--economics, political, and social-- which contribute to environmental misuse, and which are the necessary means to environmental improvement and protection.” Action needed to come from all sides and from everyone, the battle to save the environment was not a single sided issue, but extremely multifaceted and therefore needed many allies.

Part of the action philosophy was having a planned follow-through. “The University of Michigan 1970 Teach-In on the Environment, culminating a staged effort to inform and mobilize concern, can focus public attention on constructive action. Its planned follow-through can broaden and deepen the impact, carrying this urgent issue of environmental quality, with all of its implications for human life, far closer to the concerns and self-interests of all whom it touches.” The Teach-In was not enough to cause action, but ENACT itself had to cultivate change through building an ecology center and trying to pass legislation.

Radical Ecology versus Technological Solutions

ENACT sought to build consensus for environmental reform by reaching out to corporations and the University of Michigan for support, but its ecological outlook also questioned whether business and government could provide technological solutions for the pollution problems they had caused. In mid-November 1969, in a letter asking U-M President Robben Fleming for funding, the ENACT steering committee expressed alarm at the "rapid and continuing degradation of man's environment." They argued that "our technological society has not been sympathetic toward the social consequences, and has frankly ignored the ecological consequences, of industrialization." ENACT also informed Fleming that the environmental teach-in would be a prototype for the national Earth Day demonstrations planned for April 1970.

President Fleming responded with a $5,000 grant and specifically praised ENACT for its "positive approach," a likely contrast to the disruptive antiwar demonstrations by Students for a Democratic Society. The university administration's support for ENACT as a 'positive' organization also reflected its own commitment to addressing problems of public health and environmental degradation through research partnerships with corporations and government agencies. The widespread concern about the "environmental crisis" in the late 1960s and early 1970s masked considerable disagreement about the primary causes and therefore the necessary solutions. Many environmental activists and ecological groups considered the air, water, and soil pollution caused by corporations and allowed by weak government regulation to be the main problem, which then necessitated more radical remedies.

But most faculty researchers at the University of Michigan who worked on environmental issues received grants from federal agencies and often worked with corporate partners, including the Big Three automobile companies in Detroit and other Michigan-based industrial companies such as Dow Chemical. ENACT also received some funding from Ford and Dow, which illustrated its efforts to build a consensus around environmental reform but also generated criticism from radical activists. This educational video, produced by the U-M School of Natural Resources in 1970, highlighted the research partnership between Dow Chemical and U-M professors in solving the problems of water pollution. Rather than calling for population control or strict regulations on economic development, as ENACT did in its ecological mission, the film instead praised a corporation widely denounced by antiwar and environmental activists for its enlightened technological solutions.

ENACT’s political agenda and increasingly radical ecological outlook created friction with some environmental researchers on the University of Michigan faculty. George Coling, an ENACT steering committee member and graduate student in public health, remembered that most faculty in his school were “happy that they had some activist students” trying to bring environmental problems to public awareness. Coling’s advisor, Professor Morton Hilbert, was the head of the Department of Environmental Health in the U-M School of Public Health at the time of the ENACT Teach-In. A few years earlier, Hilbert had suggested a national campaign to improve public health at a federally sponsored Human Ecology Symposium attended by college students, and later in life he claimed (erroneously) that this involvement made him the “father of Earth Day.” His position paper on “Urban Environmental Health,” prepared as guidance for ENACT, adopted the traditional conservation approach of “control and management” of the built environment “with man as the central focus”--based on the belief that technological innovations such as Dow Chemical's wasterwater treatment plants could solve the problem. This outlook differed significantly from the ecological philosophy that humans should change their behavior, and that corporations and government should reduce their environmental impact, through hard choices based on harmonious coexistence with the natural world.

Morton Hilbert, like many public health experts, believed that better technology, developed through partnerships between industry and academia, could solve environmental problems. He expressed discomfort with ENACT’s rhetoric blaming government and corporations for causing the pollution crisis, instead insisting that everyone was on the same side because no one was against the environment. Hilbert later gave backhanded praise to the more radical and countercultural students inspired by ENACT: “they showed up with their peculiar dress and bare feet. They bordered on the ridiculous, but they really wanted to do something about the environment.” Hilbert also criticized the main ecological message of ENACT and Earth Day as excessively negative in a 1973 speech on “Environmental Problems,” lamenting how “the world seems to be filled with instant ecologists who constantly propose naïve solutions to complex engineering and other scientific problems.” In a rejection of the politics of ecology, Hilbert argued that “we need to focus our attention on the effect of the environment on man rather than on the oft-emphasized effects of man on the environment.” He had little patience for the “so-called environmentalists” who were “purveyors of gloom, doom, despair, and disaster. . . . Waving flags, carrying banners, and giving speeches will not solve our environmental problems.”

U-M professors who had spent their careers working with government and industry to provide technological solutions for pollution and public health hazards did not always appreciate the anti-corporate and anti-government messages of ecology activists. John Clark, a Professor of Mechanical Engineering, also criticized ENACT for allowing "extreme left-wing political views" to overshadow the "legitimate efforts toward environmental improvement" that he and other researchers had been working on for decades. Clark praised his department for working closely with the U.S. Public Health Service and the Automobiles Manufacturers Association to reduce car emissions; environmental activists were blaming the same industry lobby and government agency for leading the resistance to meaningful regulations that would decrease air pollution dramatically. For Clark, elements of the ENACT Teach-In displayed an "agonizing ignorance . . . of the vast improvements that have been brought by technological research," and too many environmental activists had become caught up in "a climate of hysteria, of shrill invective, of left-wing 'hate America' extremist politics." This uncharitable assessment did not capture the ideologically broad spectrum of speakers that ENACT recruited for the teach-in, or the careful consensus-building efforts that brought criticism from black power and antiwar groups on campus. But Hilbert's and Clark's frustration did reveal that ENACT's ecological agenda fundamentally challenged business as usual at the University of Michigan and in the world beyond.

Sources for this page

David Chudwin Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Environment: ENACT Conference 1970, Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Ecology Center of Ann Arbor Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Morton S. Hilbert Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Interview of George Coling by Amanda Hampton and Matt Lassiter, December 7, 2017

U-M School of Natural Resources, "Ecology: Man and the Environment," Part 8: "Water Pollution," Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan