National: Clean Air Legislation

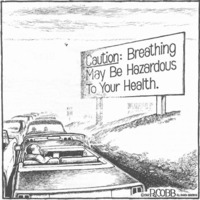

From the 1950s onwards, citizens played a crucial role in achieving air pollution control legislation by writing letters to industry officials, senators, and even the president of the United States and raising public awareness. Clean air, like clean water, became a central issue on the federal government's agenda. Further, early activism around clean air revealed the inherent tensions between government, industry, and environmentalists, which would take center stage in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Ultimately, the Clean Air Act of 1970 would prove to be one of the most significant and long-standing environmental bills in the history of the U.S., but it would take over two decades of citizen activism to gain its strength.

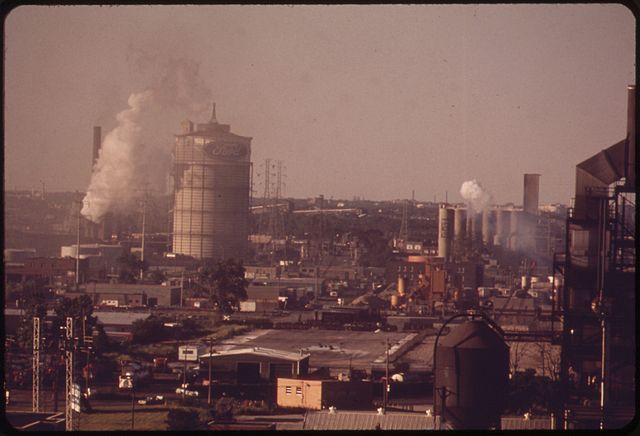

The 1950s ushered in increased public concern about the hazards of air pollution to human health and the environment. In 1953, Kenneth Hahn, a supervisor of Los Angeles County, wrote a letter to Henry Ford II, President of the Ford Motor Company, because he was "vitally concerned with the problem of air pollution" and wanted more information about the correlation between exhaust fumes and smog (top document). A Ford News Department employee responded that Ford "feels [exhaust gases]...are dissipated in the atmosphere quickly and do not present an air-pollution problem." Two years later, in 1955, President Eisenhower signed the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955, which extended later in 1959, to fund further research about air quality issues. Enforcement was left to state and local governments, while the federal government provided funds for further research. After his correspondence with Ford, Hahn continued to write to the presidents of the major automobile industries, but it became evident that "you cannot 'cooperate' or urge them 'voluntarily'" to address the automobile's burden on the air by using new equipment. Such a response would require strict and "mandatory" federal regulations on the automobile industry, as Hahn explained in this 1965 letter to President Lyndon Johnson (bottom document).

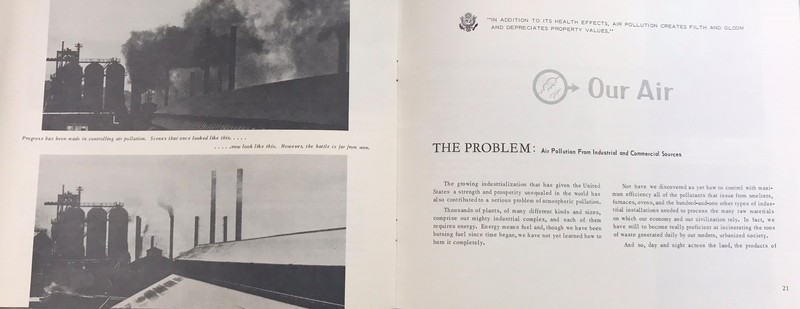

In 1963, Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1963, which encouraged still more scientific research and also expanded the role of the federal government in air pollution control. On signing it, President Johnson remarked, "Now, under this legislation, we can halt the trend toward greater contamination of our atmosphere. We can seek to control industrial wastes discharged into the air. We can find the ways to eliminate dangerous haze and smog." Congress passed several other air pollution laws during the 1960s, including the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act of 1965, which charged industries with the task of creating new models by 1968 to lessen automobile pollution, and the Air Quality Act of 1967, which had provisions in regards to regional air pollution. Heralded as the anti-pollution bill "that would actually work," the 1967 Air Quality Act assured the public that "the air crisis in the United State would soon disappear." With this confidence and relief, Congress shifted its gaze towards other issues, believing the air would soon evidence the effectiveness of the legislation. However, as air pollution continued to pervade the skies and the bodies of citizens across the nation, the federal government could not deny the visible evidence of previous bills' shortcomings.

As a result of increased citizen pressure, technical expertise, and visible pollution, many air pollution bills came under consideration in the House and the Senate in 1970. In June, the House of Representatives passed the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970, which several Congressmen believed did not go far enough, especially in regard to automobile standards. These Congressmen, therefore, proposed four new amendments to strengthen the bill, which many groups across the nation supported, including Environmental Action, the Sierra Club, the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union, and others. Environmental Action even sent out educational pamphlets and "coordinated an extensive citizens' lobby to offer amendments from the floor...[to] strengthen the section...dealing with auto emissions." Ultimately, "a parliamentary maneuver stopped [their plans] cold," and the House members brought the bill to the floor a week before it was scheduled. Because of this abrupt change, many Congressmen did not have adequate time to read over the bill or to understand the amendments suggested by the coalition of Congressmen and environmental groups. Further, it was an election year and, since environmentalism was a central issue on the national agenda at the time, it made political sense to vote in the bill's favor. The bill passed with only one opposing vote from Leonard Farbstein, the House representative who led the charge for adding stronger amendments, and thus continued on to the Senate.

Environmental Action and many other environmental organizations proved resilient in their fight for tougher air pollution control. With the aid of the legal consultant of the Nader Task Force, Environmental Action drafted an 18-point "Plan for Clean Air," which Senator Gaylord Nelson presented to the Senate and a bipartisan assortment of congressmen presented in the House. Support from the ever-increasing number of grassroots organizations, notable public figures, and the American public made up a "coalition...unparalleled in the history of U.S. environmental politics." Organizations across the country sent out newletters, such as this "Report from the Hill" from the League of Women Voters, to keep their members informed about changes in the bill and to address "problems and alternatives." Through extensive "explaining, persuading, writing, and telephoning," thousands of citizens made their opinions known to their senators, and the senators listened.

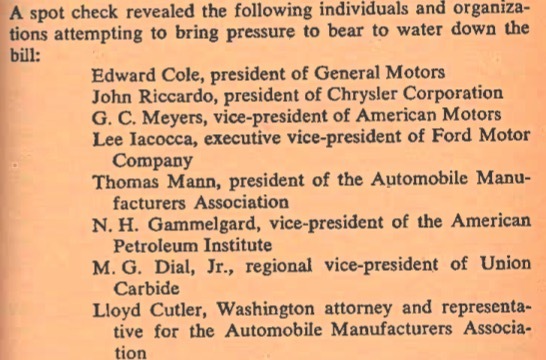

The National Air Quality Standards Act of 1970, which Senator Muskie and his subcommittee reported in August 1970, remarkably contained all but one of the provisions in Environmental Action's 18-point "Plan for Clean Air." Further, it "emphasize[d] public participation and enforcement" more than the previous bills by requiring public hearings when states set their air quality standards. When Muskie's subcommittee announced this stronger version of the bill, the Committee on Public Works held meetings "to change, accept or reject" the bill. During these meetings, the halls of the Senate flooded "with almost every industrial lobbyist in town" with the objective to weaken it.

On August 27, 1970, around two dozen lobbyists from the automobile industry arranged a meeting with the Public Works Committee at which they "rallied their most powerful resources and materials to stop the legislation from being approved." Further, they asserted that the suggested deadlines would prove impossible to meet and thus made new suggestions about the bill. The coalition of environmentalists demanded a meeting the following day at which they could reaffirm their side of the argument. The Committee granted them this request, and Environmental Action got to work, flying in representatives from across the country. Ultimately, this meeting proved to be a great victory for the environmentalists, and "the underdog environmentalists were rewarded for their vigilance." This narrative and the very bill itself favored the environmentalists from the beginning becaues "no senator could afford to oppose the Clean Air Bill when the health and well-being of his constitutents were at stake." Nonetheless, the Nixon administration supported government and industry's campaigns to weaken the bill's provisions, and thus some committee members began to rethink their decisions.

The bill passed in Congress nonetheless with very few changes to its provisions. On December 31, 1970, President Nixon signed the Clean Air Act of 1970, the most extensive air pollution law to date. Upon signing the bill in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Nixon remarked to Congress, "And I would only hope that as we go now from the year of the beginning, the year of proposing, the year 1970, to the year of action, 1971, that all of us, Democrats, Republicans, the House, the Senate, the executive branch, that all of us can look back upon this year as that time time when we began to make a movement toward a goal that we all want, a goal that Theodore Roosevelt deeply believed in and a goal that he lived in his whole life." In the midst of his grandiose statement about continuing Roosevelt's vision for conservation in America, Nixon did make an accurate projection that 1970 was the "beginning," and, therefore, the rest of the story depended on forthcoming and essential enforcement. Further amendments to strengthen the Clean Air Act passed in 1977 and again in 1990.

"Now law, the Clean Air Act Bill creates new anti-pollution weapons in the federal arsenal and increases citizen power against polluters...but the fight for clean air is not over"

-- Environmental Action

Sources

Environmental Protection Agency, Documerica Project, National Archives Catalog, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542493

Environmental Action Newsletters

League of Women Voters of Detroit Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

"Air Pollution--1967 (Automotive Air Pollution)," Part 1, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution, Committee on Public Works, U.S. Senate, February 13-21, 1967 (Washington: GPO, 1967)

Environmental Action, Earth Tool Kit: A Field Manual for Citizen Activists (Pocket Books, 1971), 309-324

EPA, "History of Reducing Air Pollution from Transportation in the United States," https://www.epa.gov/air-pollution-transportation/accomplishments-and-success-air-pollution-transportation

Richard Nxon, "Remarks on Signing the Clean Air Amendments of 1970," December 31, 1970, Public Papers of the Presidents 1970

Arthur C. Stern, "History of Air Pollution Legislation in the United States," Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association 32:1 (1982), 44-61