Lasting Water Pollution Control Since the 1970s

Great Lakes Pollution Control

Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Restoration Act 1990

In 1990, Congress passed an act that was meant to secure and defend the viability and well-being of wildlife throughout the Great Lakes. In the Act, Congress explained that the Great Lakes have fish and wildlife communities that are structurally and functionally changing. Additionally, successful management of fish, wildlife, and water resources focuses on lakes as ecosystems, and requires the coordination and integration of efforts of many partners. The Act calls for additional actions and better coordination in order to adequately protect and manage fish and wildlife resources, including habitats on which the resources depend. Lastly, the 1990 law promoted the effective partnership between federal and state (or territorial) governments by providing the funding for projects related to restoration.

Healing Our Waters

Led by the National Wildlife Federation, the Healing Our Waters Great Lakes Coalition was formed in 2004 to secure a strong, sustainable Great Lakes restoration plan, along with the federal funding required for its implementation. Its member organizations represent millions of activists and citizens surrounding the Great Lakes Basin who share the common goal of restoring and protecting the Great Lakes, the largest freshwater resource in North America. According to its mission statement, the Coalition aims to:

- "Stop sewage contamination that closes beaches and harms recreational opportunities;

- Clean up toxic sediments that threaten the health of people and wildlife;

- Prevent polluted runoff from cities and farms that harm water quality and lead to toxic algal blooms;

- Restore and protect wetlands and wildlife habitat that filter pollutants, provide a home for fish and wildlife, and support the region’s outdoor recreation economy;

- Prevent the introduction of invasive species, such as Asian carp, that threaten the economy and quality of life for millions of people."

The Coalition has roughly 145 member organizations (environmental, conservation, and outdoor recreation organizations, as well as zoos, aquariums and museums), a core staff of 6 leaders, and a governing board of 14 that actively works to provide guidance and long-term planning for Healing Our Waters. Member organizations, activists, and concerned individuals across the Great Lakes Basin region convene annually for the Coalition's Great Lakes Restoration Conference. The Coalition also is tasked with educating federal governmental officials of the importance of the Great Lakes restoration by maintaining an active presence in Washington, D.C., and by urging the public to lobby Congress to pass laws to protect the Lakes. In summarizing the Coalition's mission, its website also states:

"Engaging in equity work means that we strive to restore and protect the Great Lakes so that all of the region’s people can have accesses to affordable, clean, safe drinking water; to eat fish that are safe and not toxic; and to live healthy lives that are not undermined by toxic pollutants and legacy contaminants... Healthy lakes and healthy people go hand in hand. The Healing Our Waters-Great Lakes Coalition will endeavor to make our work more relevant and impactful and by doing so protect basic human rights, like those referenced above, for all people and communities in the region, so that the Great Lakes can be enjoyed and used by people now and for generations to come."

Mike Shriberg, the Director of the National Wildlife Federation's Great Lakes Regional Center, is also currently the co-chair of the Healing Our Waters Great Lakes Coalition. The Regional Center co-runs the coalition, which he describes as "an amazing group of environmental conservation organizations from around the region that get together for a common cause: protecting and restoring the Great Lakes." He maintains that in their short time in existence, the Coalition has been very successful in attracting over $2 billion in funds specifically for restoration. One specific recipient of the money is the reconstruction of water infrastructure, since "lead contaminating our drinking water... and raw sewage flowing out into the Great Lakes works directly to counter to our goals." There is no parallel anywhere in the country or the world that has the breadth and scope of Healing Our Waters, which happens to be run out of Ann Arbor, Michigan, right on University of Michigan's campus. Mike Shriberg explains, "Think about it from the perspective of The Great Lakes Regional Center. It started as a partnership with the University of Michigan at a time when activism was running high, and now it’s at the forefront of efforts to bring together groups across the country in this massive scale effort to restore the most important bodies of water in the world."

National Water Protection

Recreational Water Quality Critera

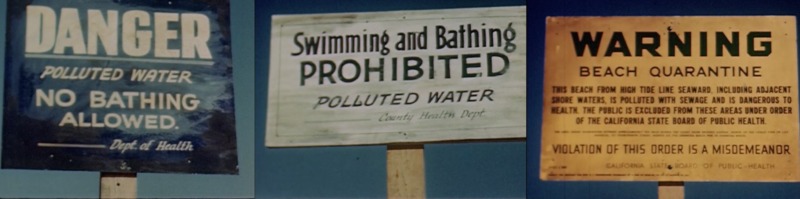

The Envrionmental Protection Agency (EPA) creates and fortifies criteria for recreational waters to protect people from microbial organisms in water, such as bacteria and viruses. Often called pathogens, these organisms are found naturally in lakes, rivers and beaches, and some may make our waters unsafe for humans. If one drinks, swims, or performs other recreational activities in untreated water contaminated with pathogens, it may make people ill. The EPA thus recommends specific criteria that limits detectable levels of microbial organisms to protect human health, and the national suggestions can be used by state and local governments as guidance when setting their own water quality standards.

1986 Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria

In 1986, the EPA issued ambient water quality criteria recommendations for recreational waters. EPA issued such recommendations under the authority of the Clean Water Act amendment of 1977. The criteria designated acceptable types and concentration levels of pollutants in the water, in part measured by gastrointestinal illness rates associated with recreational use of the water. The EPA designated recreational swimming beaches, like state run beaches supported with state funds, as needing the most rigorous and frequent monitoring and water sampling for high levels of harmful bacteria, as these waters are heavily used by the public and therefore, if unsafe, most able to impair the health of the public.

2004 Final Water Quality Standards Bacteria Rule for Coastal and Great Lakes Recreation Waters

Federal water quality standards controlling bacteria aim to protect human health for coastal and Great Lakes recreation waters. The 2004 rule established health-based federal standards for the states and territories bordering Great Lakes or ocean waters that had not yet adopted prior standards last updated in 1986. The EPA recommended certain criteria to be as protective of health as possible. According to the EPA, in 2004, of the 35 states and territories that coastal or Great Lakes recreation waters, 14 had adopted that criteria for all their coastal recreation waters, 5 had adopted the criteria for some of their coastal recreation waters, 13 were in the process of any protective criteria, and 3 had not yet started adopting any recommended criteria. When a state or territory adopts health-protective recommendations into their standards, the EPA first approved those standards, then withdrew such strict federal oversight for that state or territory. The EPA's authority comes from the Clean Water Act of 1972, which required the EPA to publish criteria and limits on certain pollutants to make coastal waters safe for swimming and other recreation. The federal law mandates states to meet these standards and impose limits on pollutants that may protect human health; for example, a criterion for a pollutant may that there can be no more than a certain concentration of that pollutant in the water, such as 10 parts per million, or else the violator will face repercussions.

2012 Recreational Water Quality Criteria

The updated Recreational Water Quality Criteria of 2012 strengthened previous regulations, as they "reflect the latest scientific knowledge, public comments, and external peer review." The criteria, once again, aim to protect the public from exposure to harmful levels of pathogens during water activities, including both primary-contact water activities such as swimming, wading, and surfing, and other activities such as fishing and boating. In comparison to the 1986 criteria, the 2012 criteria updated statistical threshold values and geometric means for pollutant levels based off studies from the National Epidemiological and Environmental Assessment of Recreational Water data. The recommendations for marine and fresh waters are no longer based on different illness rates, and urges states to adopt the standards with newly developed and validated technologies. The EPA also provided additional information on tools for assessing and managing recreational waters, such as predictive models and surveys, and informed states and terrotories on tools for developing the criteria, such as ecological studies of both marine and fresh waters.

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is one of the many water pollution control laws passed in the 1970s and one that is still powerful today. The Act was designed to protect endangered species from extinction, and preserve the environments that have been spoiled as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation." To do this, Congress declared that various species of fish, wildlife, and plants in the U.S. are now considered extinct, as they have been "so depleted in numbers that they are in danger of or threatened with extinction." The Act therefore provides guidelines for conservation of species and the ecosystems on which they depend, since scientists believed that the primary reason for species depletion was habitat loss.

Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act established the definition of the term "critical habitat" as an area essential to the preservation of a certain species. The law says that identifying "critical habitats" would lead to advancement towards recovery goals, including habitat protection and security of land, water and air. The Act allowed organizations, including both the National Marine Fisheries Service & the Fish and Wildlife Service, to designate areas as "critical habitats," and thus protected under law. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), designating an area as a "critical habitat" does not necessarily restrict further development of the area, but it is simply supposed to remind federal agencies that they must take part in special actions and efforts to protect the important characteristics of these areas.

The Act further declared that Federal agencies must cooperate with the state and local governments to resolve water resource issues, particularly those in of affected areas that need to be watched over due to presence of endangered species. For example, the Chinook Salmon species was announced as both threatened and endangered in September of 2014. The species' typical range included California, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, so waters in these areas were considered critical and were then monitored by the FWS. These waters included the Columbia River in Washington, the Sacramento River, the Snake River in Wyoming. Under the Act, Washington, California and Wyoming must comply with federal water quality regulations.

The Clean Water Rule

In May of 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers amended the Clean Water Act of 1972. Together, they jointly announced a rule that defined and expanded the scope of waters protected under the Act. The Rule revised the regulations that were established in 1972 and follows past amendments of 2001 and 2006 that interpreted the regulatory scope of the Clean Water Act more narrowly than the intended, appropriate scope of waters protected under the CWA. The new rule defines specific waters of the United States as “jurisdictional,” meaning they are subject to the multiple regulatotions and violations mandated under the Clean Water Act. Some waters, however, were deemed non-jurisdictional, and are not subject to those requirements.

According to the Congressional Research Service, the Clean Water Rule only modified some categories of waters, but left some remain as jurisdictional under existing rules: traditional navigable waters, interstate waters and wetlands, the territorial seas, and impoundments. The rule also lists which waters would not be jurisdictional, including certain cropland and ditches. Much of the controversy surrounding the Rule since the 2015 rulings has focused on the degree to which isolated waters and small streams are jurisdictional. Many of these disputable waters had needed case specific evaluations in order to determine whether jurisdiction applies; under the Rule's final guidance, less of these waters will continue to require case specific reviews, and more will be considered “waters of the United States.” The changes specified in the Clean Water Rule allowed the Clean Water Act to assert its jurisdiction for water pollution standards over more bodies of waters, enlarging authority 35% beyond the Act's prior reading.

Sources:

International Joint Commission (2014). A Balanced Diet for Lake Erie: Reducing Phosphorus Loadings and Harmful Algal Blooms. Report of the Lake Erie Ecosystem Priority.

US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Harmful Algal Blooms." NOAA's National Ocean Service. November 16, 2009. Accessed December 27, 2017. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/hazards/hab/.

"Healing Our Waters Coalition." Healing Our Waters Coalition. 2010. Accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.healthylakes.org/.

Clean Waters (General Electric Company: Wolff Studios, 1945), Prelinger Archives, https://archive.org/details/clean_waters

Claudia Copeland, "EPA and the Army Corps’ Rule to Define ‘Waters of the United States,’” January 5, 2017, Congressional Research Service, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43455.pdf

Public Law 89-234, "Amendment to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act," October 2, 1965, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg903.pdf

"16 U.S. Code § 1531 - Congressional findings and declaration of purposes and policy." LII / Legal Information Institute. Accessed December 27, 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1531.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service | Endangered Species Program. "Listing and Critical Habitat | Critical Habitat." Official Web page of the U S Fish and Wildlife Service. August 3, 2017. Accessed December 27, 2017. https://www.fws.gov/endangered/what-we-do/critical-habitats.html.

Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "Critical Habitat Actions by Listing (FWS and NMFS species)." Critical Habitat Action Search Results. January 1, 2002. Accessed December 27, 2017. https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/reports/ad-hoc-crithab-actions-report.

"Microbial (Pathogen)/Recreational Water Quality Criteria." EPA. August 21, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/wqc/microbial-pathogenrecreational-water-quality-criteria.

"2012 Recreational Water Quality Criteria." EPA. August 01, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/wqc/2012-recreational-water-quality-criteria.

"Final Water Quality Standards Bacteria Rule for Coastal and Great Lakes Recreation Waters." EPA. March 17, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/beach-tech/final-water-quality-standards-bacteria-rule-coastal-and-great-lakes-recreation-waters.

EPA. "Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria." Regulations.gov. August 13, 2007. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OW-2007-0808-0001.

Office of Water, Environmental Protection Agency, “Recreational Water Quality Criteria,” 2012, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/rwqc2012.pdf

Office of Water, Environmental Protection Agency, “2012 Recreational Water Quality Criteria,” December 2012, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/rec-factsheet-2012.pdf

"Nationwide Bacteria Standards Protect Swimmers at Beaches." EPA. October 31, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/beach-tech/nationwide-bacteria-standards-protect-swimmers-beaches.

Endangered Species Act of 1973, Public Law 93-205, December 28, 1973.