Great Lakes Activism Through 1970s

Michigan Activism

After Nixon's veto of the Clean Water Act, citizens nationwide demanded action to clean up local waste. The citizens ranged from politicians to students, and comprised of everybody in between. In Michigan, 'local waste' included the pollutants that were affecting the Great Lakes.

As explained by Tony Abar of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and Professor Justin Leonard of the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources, the general public felt that the federal government was too far removed from the water pollution issue. The 1970 University of Michigan video "Ecology: Man and the Environment, Part 11: Who Governs Nature?," explains that locals felt that they could influence local government more than state and federal, and state more than federal government. "If we want the people to feel that they can have an input to natural resources or environmental policy," Abar explains, "power] must still remain with the state or local government," as most actions can be taken at this level instead of federal.

Michigan quickly became a spot of strong political activism against environmental pollution, destruction, and neglect. In 1973, Democratic Senator Philip Hart of Michigan wrote a letter to the Director of Office of Management and Budget summarizing his discontent with the lack of federal effort in environmental cleanup at the local level. The letter questioned and pressured legislation in Washington, D.C. about the current sum of money being provided for cleanup in his state. State and local activism resulted in Congress appropriating $103.5 million to Michigan and other states surrounding the Great Lakes for pollution control activities, such as enforcement, research and demonstrations. However, Hart felt that the EPA was not spending it rapidly or efficiently. Toxic pollution such as phosphorus and nitrogen runoff caused soil erosion and sewer overflows, and resulted in the area being targeted by contaminated sediments, leading to fish consumption warnings and destruction of wildlife habitat. This letter from Hart was sent to the director of The Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Its function is to produce the President's Budget, and measure the quality of agency programs and policies. Hart requested explanation and further consideration of Congress' budget, discussing that that citizens want an accelerated clean-up program and a larger sum is necessary.

Since Hart publicized the fact that he believed change, both in the United States and in Michigan, was not happening nearly far enough or fast enough, citizens took to writing letters as an outlet for expressing their concerns. Residents, concerned families, and students had desires to voice discontent for policies, point out their lack of effectiveness, and write about their passion for change. This manifested as demand on the government. Specifically in 1973, in the wake of the Clean Water Act veto, communities across the state were looking for effective results fast; when that didn’t happen, activism arose towards cleaning up the Great Lakes, as displayed in these letters. This handful of notes, requests and complaints sent in to Senator Hart include:

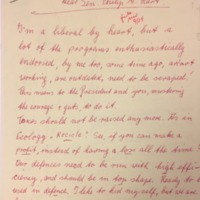

(1) A local woman demanding governmental action, claiming current laws are outdated and ineffective. This could be referring to the Clean Water Act amendment not being in full effect yet, or Federal Water Pollution Control Act passed by Congress.

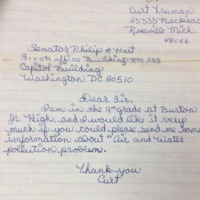

(2) A concerned student pushing for better environmental standards.

(3) A ninth-grader requesting information about Michigan's pervasive environmental problems.

(4) "A concerned person” expressing interest about wasteful polluting. Hart’s reply referred the resident to the EPA, since they wanted to know what the Hart and other governmental officials were doing to stop the problem. EPA was created in 1970, and was/is a strong player in controlling environmental issues.

Environmental Action, the organization that coordinated the national Earth Day in 1970, often published newsletters that summarized various environment-related studies, events, criticism, rules and regulations. The newsletters address environmental issues and allowed environmentalists to advocate the management of pollution through changes in public attitude and individual behavior, and through efforts to understand more clearly how we can use and enjoy clean water without depleting it. Environmental Action also used these newsletters to voice their disapproval of federal actions around standards and lack of action.

In June 1971, Environmental Action published a newsletter that outlined new dirty water reports, provided criticisms of various federal agencies, lauded bureaucrats for speaking out, and informed readers on a new ten-group alliance seeking out clean waters. Although reporting of national news and challenges, the letter cited Senator Hart, a prominent force of advocacy within the state of Michigan, the Great Lakes Basin, and the nation as a whole. Hart revealed a Dartmouth College study reporting alarming amounts of persistent pesticides found among marine fish in the Hudson River. This was one of the seemingly infinite studies published that reported details of degradation of the world's waterways, and one that Environmental Action cited to induce behavior change and action among its readers.

The June newsletter also commended Interior Department official Nathaniel Reed, who was the new assistant secretary of the Interior. Reed appeared before the House Conservation subcommittee and said that various stream construction projects of the Army Corps of Engineers are having a "devastating effect" upon American Waterways. Reed faced criticism from certain Republican congressmen, including Sam Steiger of Arizona. However, many Democratic officials such as Subcommittee Chairman Henry Reuss of Wisconsin enthusiastically called the testimony the "finest" he had ever heard. It was public accounts like these that gave hope to Environmental Action activists, who wanted to reinforce the idea that since government officials are taking action by expressing their opinions frankly and publicly, we, too, can impact policy change and attitudes by speaking out and demanding change.

Environmental Action also released "Water Wasteland: Nader Task Force Report on Water Pollution" in October 1971. The piece reviewed a new collaborative study from Harvard Law School, Water Wasteland, exposing the bureaucracy that is supposedly cleaning up America's water. In doing so, the study revealed evidence showing that our water has "actually gotten dirtier since the passage of major federal water pollution legislation" in the late 1960s. It showed how federal programs that claim to revolutionize our waste disposal methods were riddled with "inaction, delays, and downright criminal neglect." The study put the problem of water pollution in proper perspective for American citizens, showing that industry used ten times more water than municipalities. Therefore, individuals at the local level were indeed doing well in their efforts to control their volume of waste and output, but in order to complete the cleanup, the federal government needed to take charge. In vetoing the Clean Water Act, Nixon temporarily cancelled the potential for federal agencies to regulate industry pollutants with standards. Environmental Action is calling for its readers to speak out and "come out heroes" by pushing for the toughening of weak legislation by Congress and the Executive Branch.

"Will we ever have clean water?," Environmental Action's March 1971 newsletter asks. June of 1971 marked the upcoming end of the authorization for spending money under the 1965 Water Quality Act, and Nixon used the end of that authority as an excuse to revamp the billion dollar programs. Environmental Action wrote that sewage treatment lacked effectiveness and was unsuccessful in producing a desired result, leaving tons of waste completely untreated, and industries being subsidized to continue dumping their waste discharges into public streams. Environmental Action also points out that industries that do pay user fees only do so based on the quantity of their waste, not the toxicity. Water pollution legislation barely recognizes industry pollution, Environmental Action claims, and relies too heavily on complicated standard-setting procedures on the state level. These procedures were time consuming, and in the end, may not even be successful to such a high degree. As Environmental Action put it, "how was one to tell which particular plant or municipality was responsible for directly lowering the water quality of a given body of water?"

By calling for an end to the present and ineffective bills and procedures at the state level, Environmental Action was again pushing for a stronger federal regulatory role and for new patterns for federal enforcement. At the time, the grant-in-aid program for construction of waste treatment plants was lengthy and convoluted, but was the standard for regulation enforcement. Looking up, however, was a 1961 act which increased federal funding for the grant program and eliminated the obstacle to federal enforcement procedures of getting state's consent before federal court action could be initiated. Additionally, the Water Quality Act of 1965 sought administrative reorganization and established plans to implement joint federal-state quality standards. Despite these advances, Environmental Action claims, the major drawback of this system continued to be its dependence on the concept of water use designation.

It was crucial, therefore, to voice opinions on controversial actions concerning legislation among the gederal government. For example, upon the discovery of a violation, Nixon's bill proposal authorized no criminal penalties for a pollution violation. It did not make it mandatory for the EPA to act upon a discovery, and allowed the polluter to conitnue its pollution for up to 75 days, attempting to protect industry and the economy's well-being. The Senate was to begin hearings on the bills later that month in March, with industry "attempting to water down the Nixon bill," and environmentalists "favoring a strengthened bill."

Environmental Action was calling for more emphasis on effluent regulations at both the local and national level, and for administration to begin abatement procedures upon discovery of a violation. They believed penalties must match the crime if achievement of standards is desired, and felt that mandatory minimum fines should be assessed the moment the administrator detects a violation. Additionally, Environmental Action demanded that citizens should be able to report violations and receive part of the fine levied if their information leads to conviction.

This newsletter accused Nixon of attempting to allow industrial polluters to continue polluting and to legalize their activities; meanwhile, the letter used this evidence and channeled into readable terms for the general public in an attempt to spark a movement against inadequate federal action.

Great Lakes Basin Compact

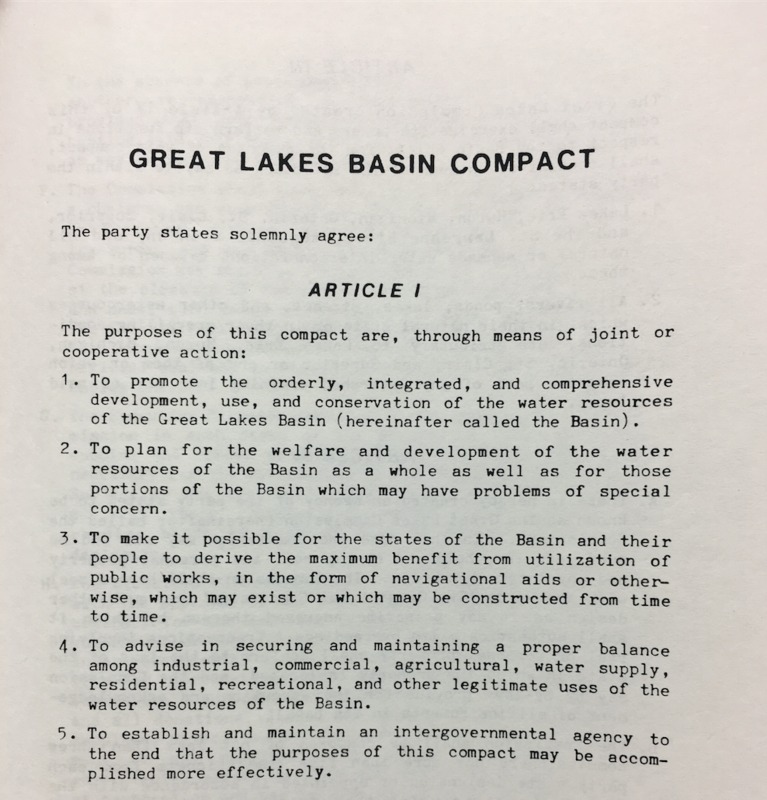

Approved July 24, 1968, the interstate Great Lakes Compact is aligned goals among Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. The compact detailed how participating states are to manage, supply, and build upon the Great Lakes Basin's water supply. It placed a ban on diversions of water out of the basin, and promoted the orderly, integrated development, use and conservation of Great Lakes water through joint or cooperative action. As noted in the photo to the right, the purposes of this compact include promoting the orderly development, use and conservation of Great Lakes Basin water resources; making it possible for the states within the Basin to derive the maximum benefit from utilization of public works; maintaining a balance among ilegitimate uses of water resources, including inudstrial, commercial, agricultural, water supply, residential, and recreational; and maintaining a governmental agency, the Great Lakes Commission, to more effectively accomplish the goals of the compact. (16) (17)

Local Efforts

Upon analyzing the plethora of presidential papers available from Nixon's administratin (1969-1974), it is clear that education the public and inspiring U.S. citizens to take action was one of Nixon's priorities. His administration focused on diverting primary responsibility for environmental consciousness away from the federal government and into the hands of locals. More than 500 of Nixon's presidential speeches, addresses and public documents from this time period are centered around the environment, and using crisis rhetoric, they were meant to rouse and energize citizens across the country. For example, the "Statement Announcing the Creation of the Environmental Quality Council and the Citizens' Advisory Committe on Environmental Quality" in 1969, Nixon began by quoting President Theodore Roosevelt, claiming that the improper use of natural resources such as water "constitute the fundamental problem which underlies almost every other problem of our national life." He continued by explaining the present threat of the availability of "good air and good water, of open space and even quiet neighborhoods." In combination with citing evidence of the declining quality of the American environment, Nixon was clearly attempting to alarm the public and strike something close to fear. In Nixon's 1970 "Special Message to the Congress on Environmental Quality," Nixon called on individual U.S. citizens to take responsibility and fight against pollution. Nixon pointed out that:

"The tasks that need doing require money, resolve and ingenuity - and they are too big to be done by government alone. They call for fundamentally new philosophies of land, air and water use...for greater citizen involvement, and for new programs to ensure that government, industry and individuals all are called on to do their share of the job and to pay their share of the cost... The fight against pollution, however, is not a search for villains."By framing individuals in the same context as the government, Nixon is inadvertently equating the two parties as having equal pasts of environmental neglect, and shared responsibilities in going about undoing them.

President Nixon also delivered a series of environmental remarks around the country, including a monumental one in Chicago, and his "Remarks in Ocean Grove, New Jersey" in 1970. These speeches served to unite its listeners and viewers and summon them to work together towards a peaceful approach to solving pollution. Nixon addresses the public as the majority and informs them that they are the ones with all the power.

"We need to clean up the air, and clean up the water... This administration offers a new approach, a new approach to the problems, one of reform, one of restoring the beauty of America, one of renewal of the American spirit. That is the spirit in which I address you today... You, the majority, can vote for those policies... not only to live in a period of peace but in a period of progress and opportunity and freedom in which the air can be clean, and the water can be pure, and the parks and the living spaces can be as they once were in this country. And that can happen. That's the promise of America. That's what we stand for. That's what we're trying to work for."Lake Erie Efforts

The “Dead” Lake and the Burning River

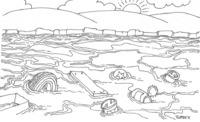

Lake Erie had become extremely polluted, largely due to the heavy industry that lining its shores in Cleveland; factories had been dumping pollutants into Lake Erie itself as well as the waterways that flowed into it, like the Cuyahoga River. The University of Michigan's School of Natural Resources publication, Ecology: Man and the Environment, Part 8: Water Pollution, well describes the entanglement of waterways and how each contributes to Lake Erie's destruction. With minimal government oversight, waste from surrounding city sewers made its way into the lake, along with fertilizer and pesticides from agricultural runoff. The pollutants contained high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen, two chemicals that contribute to the eutrophication, or premature aging, of the Lake. The resulting lack of oxygen in the water led to dead fish littering the shoreline and unsightly algae taking over the natural beauty. Once Lake Erie was declared "dead" in 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire, bringing even more negative national publicity to Lake Erie's surrounding area, specifically to Cleveland and its overly polluted rivers. Even though pollution in Lake Erie was the primary regional problem, Cleveland bore the brunt of the nation's negative attitude, as Cuyahoga's fire attracted such high levels of publicity. Images of both Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River began to gain nationwide and worldwide attention.

In the 1960s and 1970s, phosphorous levels in Lake Erie rose and led to the production of algal blooms, which severely threatened the well-being of the lake. The issue challenged scientists, troubling the public and stirring concern among government officials. Lake Erie needed to be dealt with as the persistent emergency that it was. It became evident that the Lake's degradation was not a matter for innumerable debates, further hearings, and additional scientific studies, but rather a matter that could only be addressed by immediate mobilization by local, state, and federal officials who were able to execute necessary actions and orders for a quick and effective cleanup. Government at the federal and regional levels responded vigorously in the late 70s by passing legislations and regulations to reduce in phosphorus inputs, and therefore reduce algal blooms.

According to the International Joint Commission (IJC), Great Lakes eutrophication prompted the governments of Canada and the United States to sign the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1972, which established a commitment between the two countries to reduce immense nutrient loadings and clean up the Great Lakes. Following the signing, governments on both sides of the border made significant investments to upgrade and expand municipal sewage treatment plants." Further, the government engaged in actions to reduce phosphorus concentrations in common household items. With beneficial laws put in place based off of scientific analyses and recommendations, Lake Erie began to recover quite rapidly, and by the mid-1980s, the revival of the Lake was a locally, nationally, and globally-known success story. "Lake Erie phosphorus loadings were reduced by more than half from 1970s levels," the IJC states, "and many of the problems associated with eutrophication were reduced or eliminated, confirming that reducing phosphorus loadings led to improved water quality."

Michael Rotman for Cleveland Historical says that locally, Cleveland took steps to improve its sewer system and better monitor water quality to clean up their waterways that led into Lake Erie. Cleveland's mayor Carl Stokes led the way, pledging to clean up the city's lakes, streams and rivers by speaking before Congress in 1970. He discussed the issue arising between the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie, and sought federal aid to help in the matter. Stokes' involvement resulted in the federal government stepping in to deal with water pollution in Cleveland and across the nation, and brought significant media attention to the problem, contributing to the national movement against water pollution. Additionally, Rotman explains that the “dead” lake and the burning river were major impetuses for Congress to pass the Clean Water Act in 1972, which tightened regulations on industrial dumping. That same year, the United States and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in an attempt to lower the amount of pollutants entering the Great Lakes.

Sources:

U-M School of Natural Resources/University of Michigan Television Center, "Ecology: Man and the Environment," Part 11: "Who Governs Nature," 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Philip A. Hart Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

"I'm #1 For Clean Water," Environmental Action, March 20 1971

Great Lakes Basin Compact, Great Lakes Commission, Box 7, Ecology Center of Ann Arbor records 1969-2010, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Richard Nixon: "Statement Announcing the Creation of the Environmental Quality Council and the Citizens' Advisory Committee on Environmental Quality," May 29, 1969. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2077

Richard Nixon: "Special Message to the Congress on Environmental Quality.," February 10, 1970. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2757

Richard Nixon: "Remarks in Ocean Grove, New Jersey.," October 17, 1970. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2729

Rotman, Michael. "Lake Erie." Cleveland Historical. September 22, 2010. Accessed December 24, 2017. https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/58

Skebba, Jay. "Clean up Lake Erie — now." Toledo Blade. August 5, 2015. Accessed December 25, 2017. http://www.toledoblade.com/Editorials/2014/08/05/Clean-up-Lake-Erie-now.html