Reforming the Auto Industry

"Conventional automobiles and other vehicles powered by the internal combustion engine generate 60 percent of the nation's air pollution... Since 1945 the number of cars, trucks, and buses in the U.S. has increased three-fold from 30 million to over 100 million. Estimates suggest that there will be 30 million more motor vehicles by 1980." — Environmental Action in Earth Tool Kit

By the mid-20th century, the automobile had become an essential part of the American way of life. Investments in infrastructure in the early 20th century created a sprawling highway system and the car became the only practical way for Americans to travel to and from work. Urbanization lead to higher population densities in cities, and smog filled the air. As the country became more environmentally-conscious, pollution created by the automobile became a great concern because of its consequences for the health of the public and the environment.

Reforming the auto industry became a key goal of the environmental movement. Soon after the first Earth Day, outsiders launched a crusade against General Motors by capitalizing on enthusiasm for the environment. Socially-conscious unions became critical of the industry and looked for ways to reform it from within. Under the 1970 Clean Air Act, the federal government gave the auto industry a mandate to reform. Though environmentalists lost more battles than they won, by the end of the 1970s, Americans breathed cleaner air.

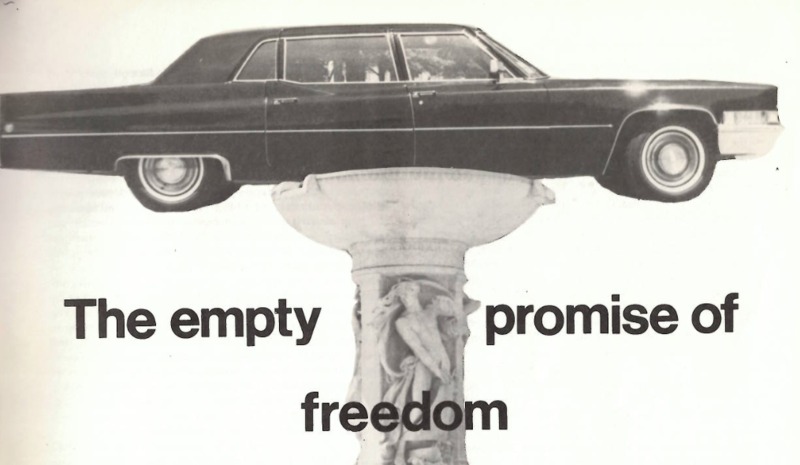

Campaign GM

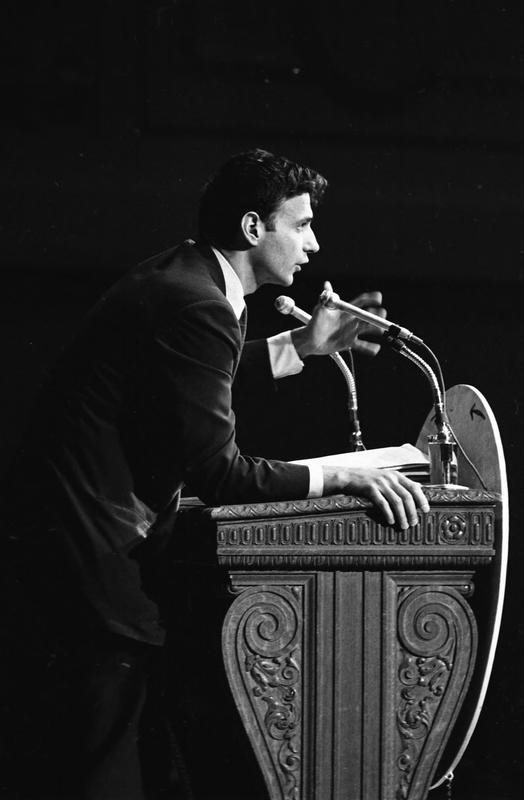

On November 30, 1965, lawyer Ralph Nader published Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, a book in which he criticized the auto industry for manufacturing unsafe vehicles that endangered the public and polluted the nation's air. The book became a bestseller in spring 1966, and in September, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Public concern had pushed new safety standards into law, but automakers still had no mandate to invest in improvements that would decrease their vehicles' environmental impacts.

Inspired by Nader’s assertion that "the roots of the unsafe vehicle problem are so entrenched that the situation can be improved only by the forging of new instruments of citizen action," a group of lawyers created the Project on Corporate Responsibility to launch campaigns to reform public corporations like General Motors. On February 8, 1970, Nader announced the group’s national Campaign to Make General Motors Responsible or “Campaign GM” which demanded that GM adopt measures to give the public a voice in its corporate policies. One of the group’s leaders summarized Campaign GM’s arguments in a letter:

“We have been concerned about the myriad ways in which General Motors’ decisions affect the lives of virtually all Americans— in areas ranging from auto safety to repair bills, environmental pollution, minority employment and worker health and safety. Too many of General Motors’ past corporate decisions have been made with eyes fixed on their short-range profitability rather than their social effects.”

Campaign GM sent General Motors a list of nine proposals addressing these concerns and requested that it place them on a proxy statement that would be sent to shareholders. GM refused, but the federal Securities and Exchange Commission ordered the corporation to include two. The first proposal would add three representatives from the public to GM's board, and the second would create a committee to study GM's contributions to issues of public concern including mass transportation, safety, and pollution. With these changes, GM, the world’s largest corporation, would become more accountable to the public.

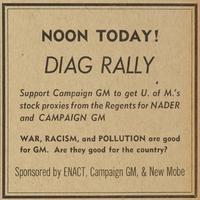

The campaign drew strength from student environmental groups on college campuses because they resonated with its anti-auto, anti-pollution message. These groups and the leaders of Campaign GM pressured universities, who collectively owned one and a half million shares of GM stock, to vote in favor of the proposals. Phillip Moore, the executive secretary of Campaign GM urged the University of Michigan "to follow up with a real commitment" its support for the environmental teach-in. Members of ENACT wrote a letter to President Fleming urging the University to vote in favor of the proposals with its 28,000 shares. The Michigan Daily endorsed Campaign GM and called on U-M to do the same:

"As long as the University continues to passively assent to GM's policies, it must share in the guilt that are the consequences of GM's actions."

Ralph Nader spoke at the March 1970 Teach-In on the Environment and used the opportunity to gather support for the campaign. Despite widespread enthusiasm for Campaign GM on campus, in late April the U-M Board of Regents decided to vote against Campaign GM's proposals to reform General Motors.

The May 22 shareholders’ meeting in Detroit lasted six hours and twenty-seven minutes, the longest in GM’s history. During the meeting, GM chairman James Roche answered questions in front of a crowd of more than 3,000—including, as the Michigan Daily reported, “a swimsuit-clad, gasmask-wearing, flag-waving woman calling for [Roche's] resignation.” Campaign GM issues dominated the meeting. The movement drew widespread attention, but among GM shareholders its support was limited. Because of this, it was unsurprising that both of Campaign GM’s proposals failed, each securing the votes of less than three percent of the 285 million shares of GM's stock.

Though the proposals did not pass, Campaign GM leaders saw their movement as successful. They had sparked a national conversation about corporations’ responsibility to act in the public interest. The meeting itself enabled members of the public to pressure GM to act. Before the May meeting, only white men served on GM’s board of directors. Several months after the meeting, GM added an African American pastor and a woman to the board. The following year, GM created a public policy committee to advise the board about the ways in which its policies contributed to problems like air pollution and safety.

During Campaign GM, an outside group tried to change the auto industry by creating public pressure. Other groups, like the United Auto Workers, tried to reform it from within.

The United Auto Workers and the Environment

Since its creation, the United Auto Workers (UAW) has used its position as the country’s largest labor union to bargain for its members’ rights to benefits like fair wages, healthcare, and retirement. Under the leadership of Walter Reuther, the UAW began to “embrace the concept of social unionism, which holds that the labor movement’s mission extends far beyond collective bargaining and narrow economic emphases,” according to labor scholar Andrew Van Alstyne. This ideology motivated the UAW to become involved in the fight for civil rights in the 1960s and the environmental movement in the 1970s.

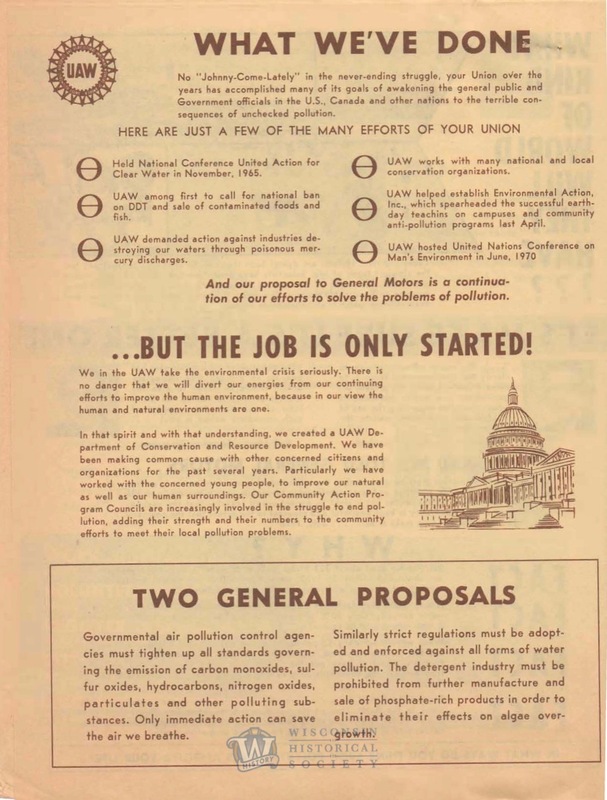

The UAW fought to improve environmental quality for a variety of reasons. UAW members worked in polluted factories, exposed to air pollution that could cause long-term health problems. In addition to its work to reduce workplace environmental hazards, the UAW argued that its members were citizens who deserved to live in a clean environment like everyone else. Environmental regulations could also affect workers' jobs, a concern that the UAW stated in a resolution passed at its convention in 1970:

“Unchecked pollution by the automobile and related industries is of direct concern to auto workers not only because they are citizens concerned for their environment but because there is a direct threat to their jobs and their job security.”

Some argued that the Clean Air Act, passed in 1970, was a direct threat to automotive jobs because its mandates to decrease vehicle emissions would cause factories to close. Auto companies used this threat of "job blackmail" to avoid compliance with the Clean Air Act, but the UAW placed environmental concerns on its agenda, arguing that the goals of protecting the environment and workers' jobs were not mutually exclusive.

For these reasons, the UAW's leadership claimed a stake in the environmental movement. The UAW supported Campaign GM and provided funds for the Teach-In on the Environment at the University of Michigan. Reuther even spoke at the event, and in a video interview about the Teach-In he expressed the need for “a follow-through meeting” to unite students, environmental organizations, and labor groups, because “it would be a great tragedy if the enthusiasm and the momentum of these Teach-Ins were dissipated.“ Tragically, Reuther died in a plane crash two months later, but the UAW continued on the path he had laid. For a week in July 1970, the UAW hosted Environmental Action and other environmental groups at its Black Lake Conference Center where approximately 200 environmental activists and 50 labor representatives developed a strategy to transform the enthusiasm for the environment into action.

As part of the strategy they developed at Black Lake, the UAW, Environmental Action, Zero Population Growth, the Sierra Club, and other environmental organizations signed a letter on July 12, 1970 urging Congress to make national air pollution standards strong enough that they that would, in effect, phase out the internal combustion engine by 1975. Environmental Action introduced an 18-point "Plan for Clean Air" in August 1970 with the UAW's support. In the Plan for Clean Air, the groups included a demand to phase out the engine, as well as a demand that the government pass legislation to strengthen air pollution standards by encouraging the development of low-polluting fuels, systematically testing new vehicles to ensure they met air pollution standards, setting high fees for industrial air pollution, and giving citizens standing in court to bring suits to enforce new regulations. Despite the radical nature of the coalition's demands, many parts of this plan eventually became part of the 1970 Clean Air Act.

"Because industry has for so long polluted the environment of the plants in which we work and has now created an environmental crisis of catastrophic proportions in the communities in which we live, the UAW will insist on discussing the implications of this crisis at the bargaining table," — Walter Reuther at the April 1970 UAW Convention.

The UAW saw its contract negotiations with GM in the summer of 1970 as an opportunity to push for stronger environmental standards in the workplace and to force the company to take action on federal pollution regulations. Governmental regulation was a direct threat to workers' job security, and the unions wanted a say in the way the auto companies approached the issue. By mid-September, contract negotiations with GM had stalled, and the UAW, seeking higher wages and better working conditions, announced a strike of nearly 400,000 GM workers. Environmental Action described the strike as an opportunity for environmentalists, students, and the union to create an alliance because “the UAW is the only organization in the world that can bring GM to a standstill.” As the strike continued, environmental issues took a backseat to more economically-pressing issues like wage increases. The UAW and GM reached an agreement in late November, but its environmental demands were not met.

After 1970, the UAW remained part of the coalition of groups brought together at Black Lake and continued to engage with environmental issues. One way the UAW accomplished this was by participating in the Urban Environment Conference.

Senator Philip Hart founded the Urban Environment Conference (UEC) in 1971 as part of an effort to shift the environmental movement beyond middle-class suburban issues to address the problems faced by poor, largely African American populations that lived in the inner-city and suffered disproportionately from pollution's effects. In this interview, George Coling, a member of the ENACT steering committee who later became a leader of the UEC, describes the conference as a "union-expressed environmental organization" that created a "coalition of labor unions, civil rights groups, and environmental groups.” By bringing together organizations including the UAW, the United Steelworkers, the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and the National Welfare Association, the UEC aimed to bring urban issues to the forefront of the environmental movement.

During its early years, the UEC advocated changes that would benefit urban communities including improving mass transit, reducing lead in paint, and improving workplace conditions. After its first few years of operation, the UEC became a non-profit lobbying organization with branches devoted to education, outreach, and fundraising. According to Coling, “the UEC’s strength in the 1970s was advocacy for improvements in occupational safety and health and in-plant pollution. We organized comments on proposed Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) rules, organized coalitions from all over the country for increased funding for OSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Health and trained thousands of women, minority and unorganized workers on worker rights and specific in-plant work hazards.”

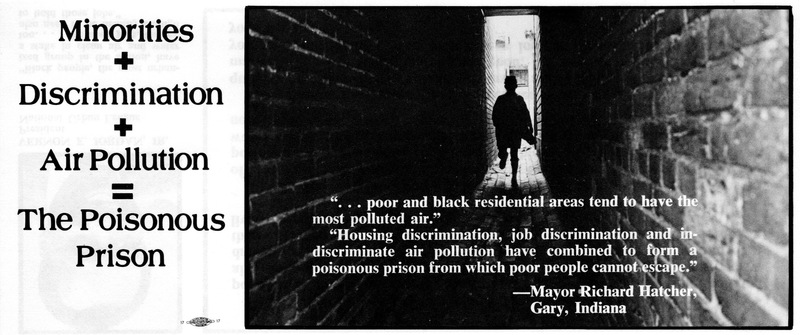

But improving workplace conditions was just one of the UEC's goals. The organization also strove to educate people about the hazards of urban air pollution. To this end, the UEC produced this brochure in 1977. The brochure combines the perspectives of representatives from the National Urban League, the EPA, and the United Steelworkers of America to explain how racial discrimination and air pollution trapped minority communities in a ”Poisonous Prison.” The brochure presents statistics that demonstrate how unevenly the consequences of air pollution are distributed and encourages readers to get involved: “We can’t stop breathing, and the problem won’t just blow away. Air pollution is a killer and it’s killing all of us. So let’s join forces to stop it. Before it stops us.”

By uniting key organizations around common goals, the UEC became an important advocate for improving the living conditions in oppressed communities, tackling issues that would later define the modern environmental justice movement.

Michigan's Auto Industry Resists the Clean Air Act

As the Senate debated the bill that would become the 1970 Clean Air Act, Senator Edmund Muskie (D-ME) said, "Detroit has told the nation that Americans cannot live without the automobile. This legislation would tell Detroit that if that is the case, they must make an automobile with which Americans can live." This sentiment is reflected in the Clean Air Act's mandate for auto companies to reduce the emissions of their 1975 model cars to 90% of the emissions produced by their 1970 model cars. In order to meet these standards, they would need to develop new technologies to curb air pollution. Auto companies argued that the standards were unattainable regardless of investments in research, while the industry's critics argued that they were not seriously committed to meeting the standards.

With the 1975 deadline approaching, GM, Ford, Chrysler, and American Motors decided to apply for a one-year extension. In a hearing on March 12, 1972, leaders of each of the Big Three testified before a Senate panel on the implementation of the 1970 Clean Air Act. In their testimony, each praised their company’s significant investments in cleaner technology but insisted that they had not made enough progress to meet the EPA’s standards.

Ernest Starkman, representing GM, noted that GM had made significant progress in the last decade-- compared to its 1960 models, its 1972 models produced 85% fewer hydrocarbon emissions and 71% fewer carbon monoxide emissions. Donald Jensen, representing Ford, testified that the company opposed the standards from the start, arguing that it needed flexibility when it came to developing new technology. He also quoted a 1972 report of the Office of Science and Technology that concluded, “Regulation should not be based upon a blind faith in technology.” He also stated the company’s position that the pollution control technologies the companies had developed were not yet reliable enough to mass produce. The costs of producing them would force the company to place the cost burden on consumers.

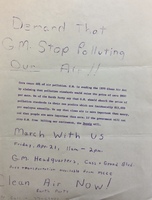

Environmental activist groups saw this appeal for an extension of the deadline as a reflection of the auto industry’s apathy toward the environment rather than a reflection of technical limitations. The Earth Party, a student group at Macomb Community College, organized a protest at GM’s headquarters demanding “Clean Air Now!” The group criticized GM for “claiming that pollution standards would raise the price of cars $900 per auto” and called for GM absorb the costs in the company’s profits instead of placing the cost burden on consumers.

EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus denied the auto companies’ appeal in May 1972. He asked the companies to renew their efforts to meet the Clean Air Act’s standards.

The EPA and environmentalists had reason to question the authenticity of the Big Three’s efforts. The Michigan Daily reported that they had “expended very little effort on research for alternative power systems,” and devoted most of their resources to the development of the catalytic converter, a device used to modify the traditional combustion engine. The companies’ claims of not being able to meet the 1975 requirements became suspect in March 1973 when representatives of the Japanese auto companies Honda and Mazda reported to Congress that they would be able to adapt their new non-conventional engines for larger-sized American cars and comply with the Clean Air Act’s requirements. This demonstrated that the standards were attainable, given a serious effort to meet them.

Citing technological limitations, the Big Three repeated their request for a one-year extension of the deadline. Ruckelshaus examined their lack of progress and granted the extension. He reasoned that the auto makers would not be able to produce vehicles that would comply with the standards by 1975 because the technology they had developed was not durable or safe enough to mass produce.

The EPA’s leniency with the auto companies coincided with what EPA spokesman John Quarles called a “liberalization” of the requirements of the Clean Air Act because of the energy crisis in 1973. The energy crisis began after oil-rich Arab countries imposed an oil embargo on the United States. The US had become dependent on oil imports to keep pace with its increasing energy needs, and the embargo caused gas shortages and price hikes. In September, President Nixon and the EPA announced a loosening of penalties for emissions from stationary sources of air pollution and an easing of restrictions on offshore oil drilling to encourage domestic energy production. Environmental Action called the developments a sign of a coming “bleak winter for environmentalists— and everyone else who breathes urban air."

Environmental Action further remarked “Nixon seems to be determined to undermine all past gains in the battle for clean air,” a conclusion it would stand behind as the energy crisis persisted into the new year. On January 23, 1974, President Nixon went before Congress to propose a “permanent framework for overcoming the energy crisis” which included provisions to “temporarily relax certain Clean Air Act requirements for power plants and automotive emissions.” He asked Congress to extend the 1975 emission requirements for two additional years so that the automobile manufacturers could “concentrate greater attention on improving fuel economy while retaining a fixed target for lower emissions.”

Congress and the EPA granted the auto industry several more extensions of the Clean Air Act's deadline because of economic and technological factors. However, the Clean Air Act's standards had been aspirational by design. In May 1973, the Wall Street Journal remarked, “When the Clean Air Act passed Congress in the closing days of 1970, the final version was so ambitious, comprehensive and stringent that even Ralph Nader was satisfied with it," The writers of the Clean Air Act aimed high in order to force industries to put more energy into developing cleaner technology than they would without a deadline. Resistance from auto companies impeded this progress, but by 1981, new cars fully complied with the standards established in the Clean Air Act.

Sources

Environmental Action Newsletters

Philip A. Hart Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.nelsonearthday.net/index.php

Environmental Action, Earth Tool Kit: A Field Manual for Citizen Activists (Pocket Books, 1971)

Environmental Protection Agency, Documerica Project, National Archives Catalog, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542493

"Implementation of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970," Part 3, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution, Committee on Public Works, U.S. Senate (Washington: GPO, 1972)

Donald E. Schwartz, The Public-Interest Proxy Contest: Reflections on Campaign GM, Michigan Law Review, Vol. 69, No. 3 (Jan, 1971), p. 419-538

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

Detroit Free Press

Wall Street Journal

Interview of George Coling by Amanda Hampton and Matt Lassiter, December 7, 2017, by remote videorecording

George Coling to Hannah Thoms, email correspondence, December 29, 2017.