V. Legacies

ENACT Organizers: Personal Stories

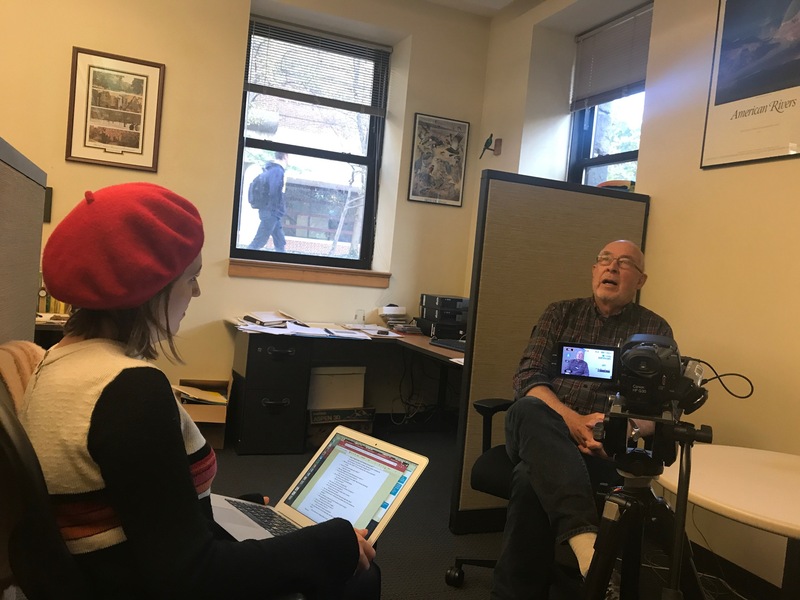

After the Teach-In, David Allan, the co-chair of ENACT, finished his Ph.D. at the University of Michigan and then later completed his post-doctorate at the University of Chicago. Upon finishing his education, Allan was hired by the University of Maryland where he would spend the first half of his career. At the University of Maryland, Allan emersed himself in fundamental science and focused on understanding the ecological interactions between species in the natural environment. While at the University of Marland, Allan was funded by the National Science Foundation, published dozens of papers, and graduated countless students. Halfway through his career, Allan shifted his focus onto the human effect on the environment. To pursue this new direction, he accepted a job at the University of Michigan in the School of Natural Resources and focused the second half of his career on application work. Throughout his career, he has served on numerous boards including the Board of Nature Conservancy for the State of Michigan and the Board of American Rivers where he worked with NGOs to provide scientific information behind their activism. After retiring from the University of Michigan, Allan began volunteering and consulting with organizations that needed his expertise. Currently, he is on the EPA Advisory Board on the Great Lakes and the Bi-National US Canadian Science Advisory Board which focuses on the Great Lakes. He also provides scientific advice to help write reports to give guidance to policymakers on the environment. He also works as a private consultant to help the environment, including legal cases involving upstream-downstream rights. Allan's career has evolved over the years, but he has continued to use his expertise to better understand the environment and improve it.

Following the Teach-In, ENACT co-chair and Environmental Action liaison Doug Scott continued his career in the environment by working as a lobbyist for the Wilderness Society in Washington, D.C. As a lobbyist, Scott worked with members of Congress to pass laws on wilderness preservation and resource conservation. Although he was helping the environment in this role, Scott missed the West Coast and accepted a job in late 1973 to be the Director of the Seattle Regional Office for the Sierra Club. A few years into his role at the Sierra Club, Scott worked as a lobbyist from 1977 to 1980 for a project focused on saving the Alaskan Wilderness, which he would later in life consider one of his greatest accomplishments. Scott continued to work for the Sierra Club for 17 years, changing roles several times. During his time there he was the Conservation Director and the Associate Director of the Sierra Club.

Elizabeth Grant, now Elizabeth Kingwill, was a member of ENACT and one of the key organizers of the Teach-In, including one of the only female leaders. In correspondence with our research team, she emphasized the concept of the tipping point--"it really was an idea whose time had come"--to explain how a small group of students at U-M became part of the rising tide of environmentalism. Kingwill observed that "we were riding on the heels of the war protests. What should be the level of anger, of emotional excess, or even violence that would get our message out? Was radicalism necessary for publicity or credibility? Including radicals but not being violent or radical was how it went. Listening to all voices and working together did work." The ENACT organizers were full-time students trying to "survive academically," Kingwill recalled; "we were those idealistic 1960s students who believed in the democratic process, with inclusivity of ideology, individuality, and creativity."

Elizabeth Kingwill believes now, more than she realized in 1970, that "a crucial part of the Teach-In was that everyone who heard that our environment was endangered also got the message that THEY COULD DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT. We gave them suggestions for acts both individual and collective that would make a difference, everything from recycling to political activism. . . . [This explains' our part of the ripple effect that went across the country in April of that year, then across the globe, to become an important part of the zeitgeist." After the Teach-In, Elizabeth Grant played a key role in the development of the Ann Arbor Ecology Center. Her vision for the Ecology Center was to create a space for existing environmental organizations such as the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, the Audubon Society, and other local, state, and national groups to meet and work together to continue to tackle the environmental issues that the Teach-In began to address. Grant then went on to receive her master's in social work and today works as a clinical therapist in Wyoming. Looking back in 2017, Elizabeth Grant Kingwill says that she hopes Americans continue to take the legacies and accomplishments of Earth Day seriously and work hard for the future of our planet instead of "letting everything go down the drain."

George Coling, a member of the ENACT Steering Committee and graduate student in public health, continued his work in protecting the environment after the Teach-In was over. He moved to Washington and led an initiative to establish ecology centers in cities and towns across the United States. With an interest in public health and humans' relationship with the environment, Coling then worked at the American Public Health Association from 1973-1974, where he focused on part on the implementation and enforcement of the Clean Air Act. He then moved to the Urban Environment Conference and stayed for nearly a decade to plan conferences focused on environment justice. Coling's career then led him to the Environmental Defense Fund where he worked on the Safe Drinking Water Act. Following his time there, he worked at the Rural Coalition from 1984-1989 where he focused on American Indian environmental issues such as acid rain and worked on adding amendments to environmental acts to include language protecting American Indians and reservation lands. He then worked for the Sierra Club where he was the Great Lakes representative in Washington, and finally he was the Executive Director at the National Fuel Funds Network. Coling also worked as an environmental consultant for numerous years. Coling is now retired in western Massachusetts and is a proud father of two adult children and a grandfather for two grandkids.

Sources

Interview of David Allan by Amanda Hampton, November 6, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Interview of Doug Scott by Amanda Hampton and Meghan Clark, November 17, 2017, by remote videorecording

Interview of Elizabeth Grant Kingwill by Maya Littlefield, November 20, 2017, by remote videorecording

Elizabeth Kingwill to Matt Lassiter, Email Correspondence, December 16, 2017

Interview of George Coling by Amanda Hampton and Matt Lassiter, December 7, 2017, by remote videorecording