Earth Day Protests and Commemorations

For the one-year commemoration of the first Earth Day, a broad coalition of environmental groups called for an Earth Week 1971 focused on local community organization to increase citizen participation in public policymaking. The call to action came from Senator Gaylord Nelson and the staff at Environmental Action, along with organizations such as Friends of the Earth, the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and Zero Population Growth. They labeled the first Earth Day an "overwhelming success" and a peaceful mass demonstration that had broadened the meaning of 'environment' to encompass civil rights and social justice issues. This agenda of environmental justice included resistance to toxic herbicides in Vietnam, attention to the "ecological tragedy of the ghetto," the preservation of wilderness areas, union negotiations for safer workplaces, and struggles against a transportation policy that neglected the public good in favor of an automobile/highway system that discriminated against the young, elderly, and poor. The Earth Week 1971 statement insisted that environmental transformation meant public pressure on corporations and the government but also changes to consumer lifestyles of ordinary Americans, to "ourselves." The coalition also portrayed the next steps as much more ambitious and daunting: to address the "global dimensions of the environmental crisis."

Environmental Action, the Washington-based organization that coordinated the first Earth Day, commemorated Earth Week 1972 with a much more sober and angry message. One year earlier, the Environmental Action newsletter had reported on the local energy of Earth Week 1971: trash clean-up and recycling drives, walkathons and bikeathons to send an anti-car message, high school protests against air pollution and endangered species, a community garden by the Ecology Center and University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. In 1972, Environmental Action headlined its report: "How the Big Boys Honored Earth Week." The organization denounced the Atomic Energy Commission for approving a new and unsafe type of nuclear power plant, criticized members of Congress who sought to weaken the National Environmental Protection Act, lamented Supreme Court decisions that sided with corporate developments in wilderness areas, and attacked the Nixon administration's support for a massive coal-fired power plant in the Southwest. The report all but called President Nixon a liar for pretending to support the environment while he obsessively destroyed Vietnam. In 1971 "the dam broke," Environmental Action concluded, and "the environmental movement was flooded with defeats."

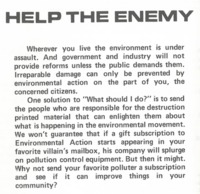

Environmental Action's combination of optimism, anger, and despair captured both the significant accomplishments and the persistent obstacles of the environmental movement in the 1970s and beyond. The Clean Air Act of 1970 was a landmark achievement, but weakened by corporate lobbying and the Nixon administration's qualified support. The Clean Water Act of 1972 passed over Nixon's veto, and federal enforcement was uneven. Citizen lawsuits remained a formidable weapon when government agencies ignored environmental impact statements or failed to enforce anti-pollution regulations, but the process was expensive and time-consuming, courts did not always rule in their favor, and politics trumped law sometimes even when they did. The energy crisis of the mid-1970s also strengthened the political backlash against environmental regulations, led by corporate lobbies that had never signed on to the agenda despite their environmentally friendly rhetoric, and conservative groups arguing that economic development and jobs mattered more than environmental protection. "Wherever you live the environment is under assault," Environmental Action warned its readers in late 1971. "Government and industry will not provide reforms unless the public demands them."

Earth Day 1980: The Tenth Anniversary in Michigan

In 1980, the University of Michigan commemorated the tenth anniversary of the ENACT Teach-In and the first Earth Day with two weeks of programming that included an environmental film festival, much attention to toxic chemicals and the Great Lakes, and an emphasis on global as well as local concerns. The events also revealed how much a decade of environmental activism on campus had transformed the U-M School of Natural Resources itself, whose graduate students had been the driving force behind the ENACT Teach-In of March 1970. The origins of SNR can be traced to 1903, when U-M established a Department of Forestry as part of the nationwide conservation movement, followed by creation of a School of Forestry and Conservation in 1927. The name changed to the School of Natural Resources in 1950, symbolizing the midcentury commitment to efficiently manage and develop water and land for the benefit of the economy. In the same year as the ENACT Teach-In, the SNR faculty overhauled the curriculum and mission to promote "resource ecology" and "environmental advocacy" as well as "resource management." During the 1970s, SNR increasingly emphasized issues of environmental justice, recruitment of minority students, and graduates trained to be "professional problem solvers in the environmental field." Faculty and graduate students at the School of Natural Resources often collaborated closely with the Ecology Center of Ann Arbor, which organized the Ann Arbor community's 10th anniversary Earth Day celebration in 1980.

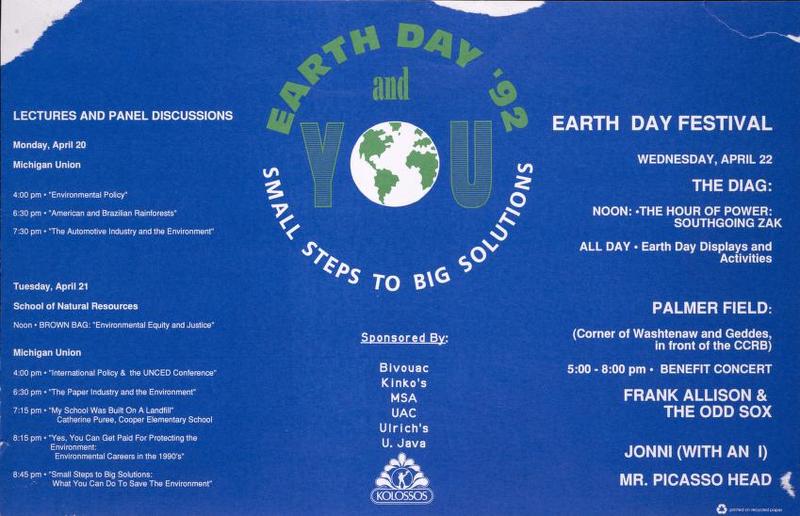

In 1992, SNR became the School of Natural Resources and the Environment (SNRE), reflecting a broadening range of missions that included working with corporations and governments to promote sustainable development, a master's program in environmental justice, and initiatives to maintain biodiversity and combat global warming. In 2017, the name changed again to the School for Environment and Sustainability, to capture an agenda to "solve the major challenges of the era, . . . . protect the Earth's resources and create a more sustainable future."

West Michigan Environmental Action Council

In the interval between its founding in 1968 and Earth Day 1980, the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC) became one of the foremost environmental activist organizations in the state, fulfilling its mission of “translating concern into action.” In 1970 the group prompted a U-M law professor to write the Michigan Environmental Protection Act of 1970 and rallied legislators and environmental groups across the state to ensure it became law. The WMEAC established foundations to fund environmental education and citizen environmental lawsuits. It initiated several MEPA lawsuits, including a contentious lawsuit over oil drilling in the Pigeon River Country State Forest.

The WMEAC organized Grand Rapids’ ten-year Earth Day celebration, titled “Earth Day on the Grand: A Change for a Lifetime.” In his remarks, WMEAC executive director Ken Sikkema proclaimed the event would “celebrate ten years of environmental progress toward cleaner air and water, a more livable city, and a balance between resource development and protection.” He also spoke about how the environmental movement had diversified and applauded it for creating hundreds of thousands of jobs. The day’s events included a community-wide clean-up of the Grand River and other public spaces, downtown walking tours, environmental films, music, and presentations.

Sikkema called the celebration a “rededication” to the environmental movement’s goals, emphasizing that “April 22, 1980… recognizes that our job is not over, nor will it ever be as long as we have to exploit nature for our survival.” Following the ten-year anniversary celebration, the WMEAC renewed its efforts to promote environmental education and legislation throughout the state. The WMEAC founded the Michigan Environmental Council in 1980 with five other environmental groups in different regions of the state. Sikkema remarked that it would provide a “mechanism needed to coordinate our activities on those statewide issues that have a high priority for all of us.” The WMEAC’s battle to save the Pigeon River Country State Forest in the 1970s led it to propose a bill in 1981 that would create a better process for managing oil and gas development on public land. Like other environmental organizations, the WMEAC tracked federal legislation, including the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, and lobbied when federal developments would affect the state's environment. The organization also created the Michigan Used Oil Recycling Program in 1979 to collect and recycle used motor oil that would otherwise be thrown away. The program started in West Michigan and expanded to cover nearly the entire state by the mid-1980s.

Sources

Political Posters, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan

Environmental Action Newsletters

Teach-Ins-Environment, Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Ecology Center of Ann Arbor Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

West Michigan Environmental Action Council Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

University of Michigan School ofr Environment and Sustainability, "History," July 2017, http://seas.umich.edu/about/history