Environmental Teach-In, Inc.

Coordinating Earth Day

Throughout the 1960s, there were environmental groups across the country, but public interest in the environmental movement was not yet clearly defined. The existing environmental groups generally focused on issues that affected their communities. However, Gaylord Nelson, a senator from Wisconsin had an idea that would bridge the gaps between these groups and define the environmental movement on a national and global scale. Nelson thought that the emerging environmental movement needed political leadership to guide to have a lasting impact. He wondered if teach-ins, which had become common because of the Vietnam War, could be an effective strategy for environmentalism. Eventually, this idea led the senator to announce April 22, 1970, as the date of a national teach-in on the environment. Nelson was apprehensive that an event organized by the establishment from the top down could be effective, so he created Environmental Teach-In, Inc. to lead the effort.

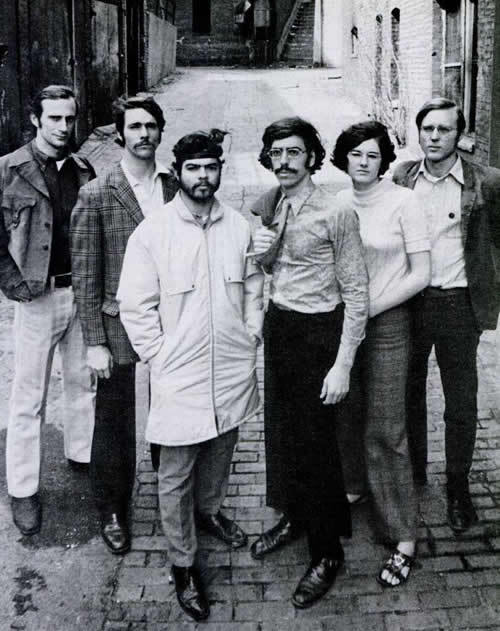

The Environmental Teach-In, Inc. staff was filled with young and motivated activists from a variety of backgrounds. In 1969, Denis Hayes, a student at Harvard, flew to Washington for a courtesy meeting with Gaylord Nelson to talk about organizing a teach-in at Harvard. This fifteen-minute courtesy meeting extended over several hours. Nelson initially instructed Hayes to organize the teach-in at Harvard and several other locations on the East coast, but several days later, the senator asked Hayes if he would drop out of school to organize the teach-in across the United States. He became the national coordinator. Hayes brought Andrew Garling and Stephen Cotton with him from Harvard to serve as Northeast coordinator and media coordinator respectively. Barbara Reid, the Midwest coordinator, was a graduate of the University of Michigan who had already been working in Washington at the Conservation Foundation. Sam Love, the Southern coordinator, came from Mississippi State University and had been involved in civil rights activism. Arturo Sandoval had been a Chicano rights activist prior to accepting a position as a coordinator of Environmental Teach-In, Inc. The youthful nature of the staff and their diverse activism backgrounds helped give Environmental Teach-In, Inc. a sense of legitimacy as they tried to organize Teach-Ins on college campuses across the country.

Environmental Teach-In, Inc. was a young, relatively radical organization. They realized that if environmentalism was going to take root, there would need to be a major shift in society's priorities. They saw the environmental crisis as "natural backlash" against humanity's indifference towards ecology so they wanted to awaken the nation's ecological consciousness and move society towards "doing life right." For Environmental Teach-In, Inc., human ecology was a way of looking at life that involved economics, science, community organizing, ethics, and even spirituality. The environmental movement was new, growing, and diverse in opinion; in order to successfully coordinate an event like Earth Day, Environmental Teach-In, Inc. had to work together with organizations across the country that may have viewed the issue differently. Earth Day would serve as a reminder of the dire consequences that environmental issues could cause if left untreated and also as a demonstration of what could be accomplished if environmentalists across the country worked together.

One of the first major decisions made by Environmental Teach-In, Inc. staff was to ditch the teach-in moniker and change the name of their big event to Earth Day. This kind of language was too associated with radical war activism and also limited the application of these teach-ins strictly to college campuses and academics. According to Hayes, the goal of the organization was to "involve an entire society in a rethinking of many of its basic assumptions." They decided to change the name to Earth Day, which resonated with people on a deeper level. During this time, the staff also moved to a new office, which was intentionally nondescript so as to portray the organization as a scrappy, but dedicated upstart.

As the first Earth Day approached, the Environmental Teach-In office staff functioned as a catalyst for the movement by encouraging people across the nation to plan events. They collected and distributed information to their contacts. According to Barbara Reid, they had the ability to turn people into activists. Requests for assistance piled in and the staff spent countless hours on the phone with students and activists across the country providing as much guidance and information as possible. The staff was incredibly busy, but occasionally they would take a more hands-on approach to organizing events in larger cities. For example, Barbara Reid brought together civic leaders and activists in an effort to mobilize the people of Chicago for Earth Day.

Earth Day highlighted to everyone the scope, breadth, and depth of environmental issues. Prior to the coordination and organization of the national teach-ins, there were numerous different movements fighting for many different environmental causes. The primary aim of Earth Day was to bring these organizations together and create a politically powerful mass-movement. Environmental Teach-In, Inc. coordinated events across the nation, but the real burden of planning and executing each event fell to local organizations and campus groups.

Sources for this Page

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation.

Environmental Action Newsletters

Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement, Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.nelsonearthday.net/collection/

Interview of Barbara Alexander (Reid) by Kiegan White, November 9, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Interview of Denis Hayes by Kiegan White, November 9, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Interview of Peter Harnik by Kiegan White, December 8, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan.