Citizen Lawsuits

Northern Michigan, a place rich in natural resources and natural beauty, became the arena for early land-use lawsuits filed under the 1970 Michigan Environmental Protection Act as newly discovered oil and mineral deposits drew developers to the region’s interior and the growing tourism industry attracted people to the coasts. Michigan's many environmental activist groups monitored the agreements that the Department of Natural Resources reached with land developers. When they became concerned about the environmental impacts of these agreements, they filed lawsuits under MEPA. John Tanton v. Department of Natural Resources was one of the first and provides an example of how MEPA gave the public a new window into state agencies’ decision-making processes. Later, in West Michigan Environmental Action Council v. Natural Resources Commission, a coalition of citizen activist groups questioned a state agency using MEPA, became part of negotiations about land use, and protected a state forest from destruction.

Protecting Monroe Creek: John Tanton v. DNR

Monroe Creek, a small tributary of Lake Charlevoix, became the focus of one of the first MEPA lawsuits. In 1970, Francis Shelden, a land developer based in metro Detroit, applied for permission to dam Monroe Creek to create an artificial lake surrounded by a subdivision with 1300 housing lots near East Jordan. In exchange for approving the development, Shelden offered to trade 40 acres of land to the State. After preparing an Environmental Impact Statement, the DNR approved the proposal in November 1971. In the DNR press release on the left, DNR Director Ralph MacMullan stated that if the land were public property he would have preferred to leave it undeveloped; however, since the land was privately-owned, the DNR’s goal would be “to control its development in such a way as to provide benefits to the public and fair and just treatment to the present owners.” MacMullan emphasized that the DNR considered each case on its own merits and that this decision would not set a precedent for future cases.

John Tanton, an ophthalmologist and leader of the Petoskey chapter of the Sierra Club, decided to take action after reviewing the DNR’s Environmental Impact Statement. On December 2, 1971, Tanton filed a lawsuit against the Department of Natural Resources under MEPA, alleging that the DNR had approved the permit despite an environmental impact statement that found that the development would cause environmental damage. Francis Shelden's housing development would result in “destruction of the only winter deeryard in a five township area; destruction of winter habitat and shelter for rabbits, grouse, and many other non-game animals as well as the destruction of a small top quality trout stream.” Although Tanton wanted to protect Monroe Creek, he also hoped that his suit would force the state to develop a new land-use policy to guide future decisions, instead of continuing to make decisions on a case-by-case basis.

It is worth noting that Tanton's concerns about increasing rates of immigration to Northern Michigan influenced his decision to file the lawsuit. A December 1971 article in the Petoskey News-Review reported that “Dr. Tanton feels that these developments will bring more crowded highways, crowded beaches, and other crowded facilities as well as the problems of the urban areas the people are attempting to flee.” Alarmed by Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb (1968), which warned that uncontrolled population growth would devastate the environment and human society, Tanton began to see immigration to his Petoskey community as undesirable. After Tanton v. DNR, through leadership positions in Zero Population Growth and the Sierra Club, Tanton encouraged traditional conservation organizations to oppose immigration as an environmental issue. In 1979, he founded the Federation for American Immigration Reform and devoted the remainder of his career to its hard-line anti-immigration agenda. Although deterring immigration was not an explicit goal of Tanton’s case in 1971, he would have considered it a desirable outcome.

MEPA empowered citizens to file environmental lawsuits, yet it remained an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. Seeking financial and legal support, Tanton wrote a letter to Joan Wolfe, the chair of the Western Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC) to request assistance from the Michigan Environmental Protection Foundation (MEPF), a branch of the WMEAC that supported environmental litigation. With the aid of the MEPF, donations to the Monroe Creek case would be tax-deductible. Shortly after, Trout Unlimited, the Eastern Michigan Environmental Action Council, and Michigan United Conservation Clubs joined the suit, demonstrating their concern for both the Monroe Creek development and the future of land-use cases throughout Michigan.

In 1972, Joseph Sax, the author of MEPA, published a report about the potential significance of several early cases filed under the law. In a section about Tanton v. DNR, he identified weaknesses in the DNR’s decision-making process:

“Dr. MacMullan's testimony indicates that the DNR does not condition the granting of its permits on the basis of what is the best environmental plan for the area, but rather on the basis of what the DNR thinks might happen if the permit were denied. This approach requires the Department to engage in far-reaching speculation… Does the Act permit the DNR to make a "lesser evil" environmental decision, or must the Department use its permit-granting authority to evaluate the environmental impact of the particular plan before it?”

On December 30, 1972, Judge Charles Brown ruled in favor of the developer, agreeing with the DNR’s judgment that the environmental consequences of the Monroe Creek development were not significant enough to justify blocking it. Tanton reflected on the case in the newsletter reproduced on the left, writing that it would have "an impact on the whole process of approval of dam permits" by making the decision-making process more public. Tanton and the environmental activist organizations that joined his case decided not to appeal the case because “it was felt that the chances for success were too small, and the risks to the Environmental Protection Act too great.” Despite being ultimately unsuccessful, Tanton v. DNR enabled a single citizen to question the decisions of a state agency, revealing weaknesses upon which later citizen lawsuits would build.

Saving Pigeon River Country: WMEAC v. NRC

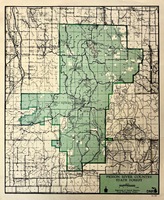

The Pigeon River Country State Forest, a nature preserve covering nearly 100,000 acres of land in the northern lower peninsula, has great value to the state of Michigan as a site of recreation and as a potential source of wealth. In 1968, the state Natural Resources Commission leased the mineral rights of nearly ninety percent of the forest to oil and gas companies. Two years later, Shell Oil Company discovered massive oil reserves beneath the forest, setting the stage for a fight over the future of the Pigeon River Country State Forest that would last more than a decade. The Department of Natural Resources, tasked with managing the responsible use of state resources while protecting them for the enjoyment of future generations, stood between the oil companies that sought permits to extract the oil and the environmental activist organizations that sought to protect the forest from harm.

Naturally, this became an issue of tremendous concern for environmental activist groups across the state. Joining established groups including the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC) and Michigan United Conservation Clubs, a new group called the Pigeon River Country Association (PRCA) formed in June 1972 and devoted itself to working with the DNR to develop a management plan for the forest. In this flyer produced in 1973, the PRCA calls Pigeon River's "undeveloped woodlands" Michigan's "most valuable prize." It asks concerned readers to contribute to the PRCA's growing court costs through the Michigan Environmental Protection Foundation so that the PRCA could "continue its watchdog role, carefully guarding the woodlands and wildlife of the area from exploitation." In the years since the MEPF had intervened in Tanton v. DNR, it had become an established organization with the resources to handle several cases at once.

At the request of Governor William Milliken and the Michigan Environmental Review Board, the DNR created and released this Environmental Impact Statement in December 1975. The statement assessed the potential biological, economic, and social effects of oil development in Pigeon River Country. It found that the forest’s elk population, which would become a central concern in the legal battle that followed, would face a “significant adverse impact” if the proposed development proceeded.

After reviewing the Environmental Impact Statement, the PRCA and other environmental organizations recommended a no-drill policy in the forest, although they recognized that drilling on the land could not be completely prevented. Because of this, they sought to mitigate damage by becoming involved in negotiations about the use of the land. Members of the public also spoke out against the proposed oil drilling, including Beth Katz, a self-described “suburban housewife, citizen, and mother” who wrote this in a letter to the Michigan Environmental Review Board:

“The dominant feeling I have is fear. I fear for my children and my grandchildren and everybody else’s. But I also have hope. It is hope which motivates this letter… The battle to save the Pigeon River Country State Forest is but one small but very significant struggle to save Nature from its conquest by forces of economic growth and urban-industrial expansion...With the irreversible destruction of each additional foot of wilderness, with the extinction of each living species, with the loss of each soggy patch of wetland, we all get a little closer to our own ultimate extinction”

Citizens' mounting concerns about the loss of public recreational land to private developers led to the enactment of the Kammer Recreational Land Trust Fund Act of 1976. The Act created the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund and required all royalties from the lease and sale of state-owned land to be placed in the trust fund for the purchase of land for recreation. Environmental groups viewed the fund positively, as indicated by the perspectives expressed in this video about the Pigeon River controversy. Tom Washington, executive director of Michigan United Conservation Clubs, said “the people of Michigan stand to gain on all fronts from this program,” and David Smethurst, chairman of the Pigeon River Advisory Council, called it “a great idea” but stressed the importance of continuing to fight for Pigeon River Country.

As the DNR came closer to approving oil drilling permits, it became apparent that environmental groups would need to do more to protect the forest. Joseph Sax understood the case’s potential significance and urged his former student Roger Conner, who had become the director of the WMEAC, to take action.

“I am persuaded that the issue is not only important in itself, but that it also represents a major precedent-setting event in the administration of some of our most important environmental laws and in the directions Michigan’s DNR is going... It is essential to keep in mind that this is no minor development. It is an industrial venture involving much more than a billion dollars, and it involves tens of thousands of acres of the State's prized recreational and wildlife habitat land... Our forest and parklands are not securely protected by our statutes. DNR is not a strong pillar of protection; it is weak and needs the most vigorous sort of encouragement to engage in good decision making. There will never be a better opportunity to make informed public participation a reality.”

Sax's prediction would come true in June 1976, when the DNR reached an agreement with Shell, Amoco, and Northern Michigan Exploration to allow “restricted, very tightly regulated oil and gas exploration and development in the southern one-third of the Pigeon River Country State Forest.” In this August 1976 news release, DNR director Howard Tanner emphasized the strength of protective measures written into the agreement. Environmental groups remained unconvinced that the measures would be enough.

Voices of the Pigeon River Controversy

Concern about the future of Pigeon River Country spread throughout Michigan, even reaching the campus of the University of Michigan. In 1977, the U-M Pigeon River Country Association held an event to spread awareness and produced a film featuring interviews with many of those advocating for and against oil development in the forest.

This segment features the perspectives of DNR Director Tanner and John Miller, a representative of the Michigan Oil and Gas Association, who describe their reasons for supporting the oil development agreement. Miller remarked that the recent energy crisis and decline in domestic energy production made oil development in Pigeon River Country essential. He also viewed development as the DNR's only ethical option because the state had already leased the land to the oil companies.

Director Tanner conceded that hydrocarbon development in the forest would lead to “damages to certain elements of wildlife” but said he was optimistic because the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund arose from the controversy. After considering the perspectives of all groups involved, Tanner had selected the plan he believed was the best option. “My principal concern is that the Pigeon River be a better place, a more beautiful place, a quieter place, a larger place, a more productive place, when we finish than when we began.”

Environmentalists did not share Director Tanner’s optimism. They offer their perspectives in this segment from the same video that featured Miller and Tanner. Former DNR wildlife biologist Ford Kellum expressed the popular opinion that “the sounds and smells of industry” would ruin the aesthetic value of the forest. Jim Knight, an authority on elk, described the forest’s herd as “a kind of environmental barometer” and could not guarantee that the herd could recover if development disrupted it.

Again, Joseph Sax objected to the development, which he saw as a rushed response to the country’s “energy crunch.” Although he recognized some oil development was necessary, he was concerned that the state had no process set up to judge which lands should be preserved and which should be developed. With “a million and a half acres of State land under oil and gas lease,” recreational land had become some of the most valuable in the state. Sax concluded, remarking, “the US Court of Appeals, in a related case, said that the Department of Natural Resources had made a major policy blunder in its dealing with oil development on its own lands.” The DNR’s decision to allow oil drilling showed that “rather than correcting the blunder, they’ve continued to blunder.”

MEPA in Action

Environmental groups hoped that the Michigan Environmental Protection Act would be strong enough to resolve the DNR's "blunder." On October 28, 1976, Roger Conner filed a suit under MEPA against the Natural Resources Commission and the oil companies on behalf of the Pigeon River Country Association and West Michigan Environmental Action Council. The groups hoped that the lawsuit would prevent oil drilling and force the DNR to produce a more comprehensive environmental impact statement. However, Ingham County circuit court Judge Thomas Brown denied their request for an injunction and ruled that the plaintiffs had not proven that the environmental impacts of development were significant enough to prevent future drilling in the forest.

Director Tanner approved permits for drilling at ten sites in Pigeon River Country Forest in August 1977, and soon after, Conner returned to court to file another suit under MEPA, this time with the support of a larger group of organizations referred to as the Pigeon River Defense Coalition. Again, Judge Brown refused to grant an injunction against the drilling, ruling that the plaintiffs had not proved “pollution, impairment or destruction” of the forest, the standard required under MEPA. Shell immediately began work, clearing four sites and one exploratory oil well. Conner appealed the case to the Michigan Supreme Court which ordered Shell to stop the drilling while it heard arguments.

On February 20, 1979, the Michigan Supreme Court reversed Judge Brown’s decision in a 4-3 vote, explaining that he should have exercised independent judgment instead of deferring to the DNR’s assessment of the development's environmental impact. The Court ruled that the risk to the elk population was great enough to stop drilling on each of the ten well sites approved by Director Tanner.

Though the Pigeon River Defense Coalition won the court case, the conflict was far from over. The oil companies filed a lawsuit of their own and the circuit judge ruled that drilling could occur in Pigeon River Country, just not on the ten sites specified in the Supreme Court decision. In April 1980, Michigan legislators supported by the oil industry introduced a bill designed to exempt oil and gas drilling from MEPA and other environmental laws. The bill alarmed members of environmental organizations, who feared that battle to save Pigeon River Country would weaken MEPA, the tool they had fought to gain. With this in mind, Ken Sikkema, the new director of the WMEAC, began to develop a compromise with the DNR and oil companies that would allow supervised drilling on the state forest. The compromise aimed to minimize environmental impacts by requiring drilling to occur as quickly as possible under the watch of the DNR and provided room for public input.

The decade-long conflict over the Pigeon River Country State Forest had reached a resolution. Though the Pigeon River Defense Coalition could not protect the forest from oil development, its intervention helped limit the risks to the environment. This case proved that, with enough passion and resources, citizen groups could use MEPA to influence state agencies' decisions. The controversy resulted in the creation of a new model for natural resource management and the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund, which continues to preserve land for public use. The herd of elk continues to roam the forest.

Sources

John Tanton Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

West Michigan Environmental Action Council Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

University of Michigan Pigeon River Country Association, "Pigeon River Forum" (1977 documentary film)

"Review cottage impact," North Woods Call, December 1, 1971

"Tanton asks court block Monroe Creek Swap, Dam," Petoskey News Review, December 9, 1971

"Key trial begins in fight between developers, ecologists," The Grand Rapids Press, January 13, 1972

Joseph L. Sax and Roger L. Conner, "Michigan's Environmental Protection Act of 1970: A Progress Report," 70 Mich. Law Review (1971), 1003-1116

Daniel K. Slone, "The Michigan Environmental Protection Act: Bringing Citizen-Initiated Environmental Suits into the 1980's, 12 Ecology Law Quarterly (1985) 271-362

"DNR asked for statement on Pigeon River drilling," Traverse City Record, August 26, 1975

Dave Dempsey, “Saving Places,” in Ruin & Recovery: Michigan's Rise as a Conservation Leader (University of Michigan Press, 2001), 201–207.

Dale Clarke Franz, Pigeon River Country: A Michigan Forest (University of Michigan Press, 2008), 101-112

Michigan Daily Digital Archives