Environmental Justice

As evidenced by ENACT’s conflicts with the black community during the teach-in at the University of Michigan, environmentalism was met with some skepticism from some sides of minority communities. Similarly to the Anti-Vietnam War protesters, they thought that environmentalism might shift the national attention from their issues onto the environment. Through their newsletter and their actions, Environmental Action did their best to fight the civil rights battle from an environmental perspective. Environmental Action had long been an ardent supporter of environmental justice issues. In his Earth Day 1970 speech, Gaylord Nelson said “Environment is all of America and its problems. It is rats in the ghetto. It is the hungry child in a land of affluence. It is housing that is not worthy of the name; neighborhoods not fit to inhabit.” The thing that Nelson and EA wanted people to understand about the environmental movement was that the very nature of environmental issues meant they had the potential to impact every level of society, from the rich to the poor. Environmental Action even claimed in newsletter articles that it affected poor and minority communities with disproportional severity.

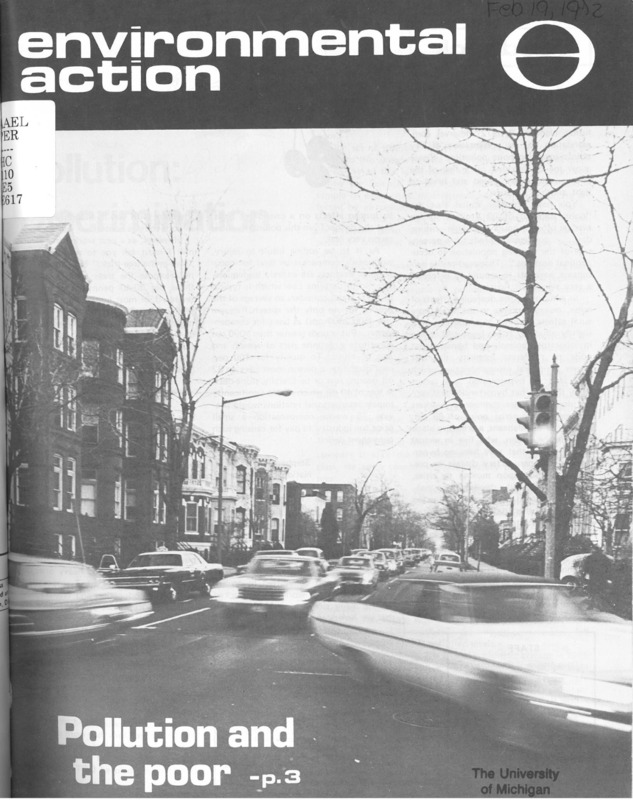

According to Environmental Action, environmental issues affected poor people disproportionally to the affluent. In the inner cities, concentrations of pollution could greatly exceed federal standards and noise pollution could far surpass reasonable levels and have a detrimental effect on a group of people who have no ability to remedy their situation. EA cited studies by the US Departments of Health and Education which showed that concentrations of pollution in inner cities constituted rampant violations of the 1970 Clean Air Act. For example, in New York City “virtually all poverty areas fell within the ring of the highest pollution levels.” These problems were difficult to address because of vested interests. If any of these problems were to be fully addressed, it would step on the toes of large-scale enterprise in some way. The number one culprit was the highway transportation lobby. Increased dependence on large highways would increase urban congestion and pollution, which would, in turn, drive the affluent to the suburbs. The poor, who are unable to flee because of discrimination, or simply because they cannot afford it inherit the inner-city. Property value decreases, which would compound their problems.

Another environmental justice issue that EA tackled in their newsletter was Native American land rights. In 1971, a Senate Interior Committee meeting in Albuquerque pitted utility company officials against Indian spokesmen. A proposed coal-burning plants in the region threatened to traumatically affect the culture of the Navajo and Hopi Indian tribes by industrializing their homelands. Environmental Action publicized the issue to develop a national citizen's campaign to support land rights for the Indians. Similarly, Environmental Action took issue with Native land rights in Alaska when a 1971 house bill threatened to detrimentally affect future Native claims to public land. The bill was a settlement supported by oil companies that offered permanent territories and monetary compensation to Natives if they relinquished their rights to other Alaskan territories. Environmental Action believed that Native Alaskans were getting a raw deal and also that the environment would suffer if oil companies got their hands on the land. For the EA staff, civil rights issues and environmental issues were intrinsically connected.

Members of Environmental Action felt that the activism of the 60's could be connected. For them, civil rights, anti-war, and environmentalism were all emblematic of systemic problems with society. Gaylord Nelson's Earth Day speech in Denver tried to convey this message. He said " Our goal is not just an environment of clean air, water, and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all other human beings and all other living creatures." Similarly, Barbara Reid became involved because she thought that environmental activism could provide a methodology to involve people in social change movements. Peter Harnik also believed strongly in the need for improved racial equality and did his best to fold that into Environmental Action's message.

Sources for this Page

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation.

Environmental Action Newsletters.

Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement, Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.nelsonearthday.net/collection/

Interview of Peter Harnik by Kiegan White, December 8, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Interview of Denis Hayes by Kiegan White, November 9, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan.