"Environmental Crisis" in the Late 1960s

During the late 1960s, an “environmental crisis” took shape as a series of environmental catastrophes and revelatory books transformed the American environmental consciousness. Soon before the crisis took its final form, several immensely popular books including Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring and Ralph Nader’s 1965 Unsafe at Any Speed pushed the public to question the relationship between the government, tasked with protecting the public interest, and industries, incentivized to act in their own economic interests. Pervasive smog in New York City and Los Angeles, the Santa Barbara oil spill, and the Cuyahoga River fires made headlines and frightened Americans across the country. Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb (1968) connected the dots and helped the public realize that the issues were all related: an exponentially growing population meant an increasing demand for limited resources, which led to unwise decisions about resource use. Driven by fear and empowered with information, the American public was poised to demand change.

Smog in Los Angeles and New York City

Nearly 100 million vehicles filled American roads by 1970, producing more than half of the country’s emissions of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide. In the 1960s, the US did not yet have strong air quality standards, and the emissions of automobiles and industries polluted the air, sometimes resulting in deadly smog. Smog occurs when the compounds that vehicles, power plants, and factories emit interact with sunlight in the atmosphere to create ground-level ozone which can exacerbate respiratory diseases including asthma, bronchitis, and emphysema. Smog production depends on weather conditions but affects those living in cities most severely because of the high density of vehicles and industries found there. In the late 1960s, Los Angeles’s persistent smog problems and deadly smog events in New York City drew public attention to the consequences of air pollution.

Los Angeles County was home to approximately 4 million cars by the mid-1960s. Because Los Angeles is in a basin, automotive emissions hung in the air and smog became a part of daily life. Public concern about the health effects of smog prompted several groups to mobilize around the issue. A group of Beverly Hills housewives formed Stamp Out Smog in the 1950s and drew attention to the city’s problems through demonstrations in which they wore gas masks. At one media event in 1964, the group’s president cut a cake celebrating smog’s twenty-first birthday. Stamp Out Smog and other groups did more than protest—they lobbied city and state officials. As a result of citizen pressure, California enacted the country’s toughest automotive emission standards in the late 1960s. Los Angeles’s air quality improved gradually, though smog continued to plague the city.

New York City, the country’s economic center, suffered from smog under certain weather conditions. Two of its most severe smog events occurred in the Novembers of 1953 and 1966 when, as an article in the EPA Journal reported, “Indian summer heat inversions trapped the chemicals and particulates from industrial smokestacks, chimneys, and vehicles that crammed the city streets, keeping the pollutants from rising.” The 1953 event closed at least two airports, caused respiratory distress among many New York residents, and was later linked to the deaths of between 170 and 200 people, though at the time its severity was not known. Thirteen years later, a similar smog event occurred over Thanksgiving weekend, again linked to the deaths of about 200 people. This event was more widely-publicized, thanks to a growing awareness of the health effects of air pollution, and caused people across the country to connect these severe events to the pollution in their communities. As a result, air quality emerged as an issue of great concern for the growing environmental movement.

The Santa Barbara Disaster and Cuyahoga Fire

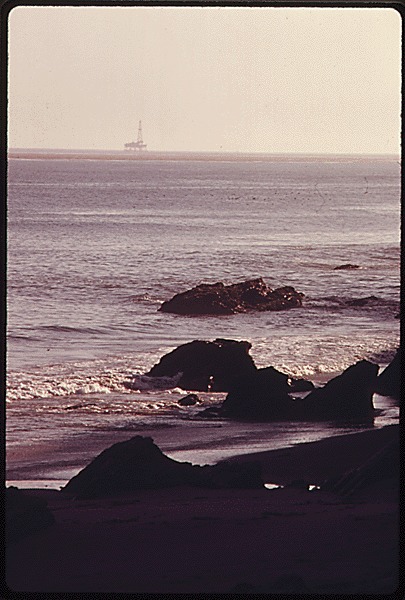

In January 1969, a Union Oil drilling platform exploded off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, dumping around 100,000 barrels worth of crude oil into the ocean, killing wildlife and washing up on the beaches enjoyed by coastal residents. The episode received massive local and national media coverage, outraged public opinion, and contributed to a widespread sense that Southern California was "losing the fight against pollution of its irreplaceable water resources," in the words of the Los Angeles Times. Local politicians, residents, and environmental organizations had already been demanding action to address the smog crisis, chemical toxins such as DDT, and pollutants in the drinking supply. Investigations revealed that industrial drainage was washing up on Venice Beach, the Greater Los Angeles Zoo was flushing raw sewage directly into the Los Angeles River, and corporations were dumping solid waste into the Inner Harbor. And then during January-February 1969, the residue from the Santa Barbara oil spill covered more than 35 milies of Southern California coastline and had a catastrophic ecological impact. This episode created a public outcry, placed oil corporations on the defensive, and inspired politicians at the local, state, and national levels to take action. The state of California strengthened its environmental regulatory agencies, including fines for corporate polluters, and enacted a moratorium on new offshore oil drilling platforms.

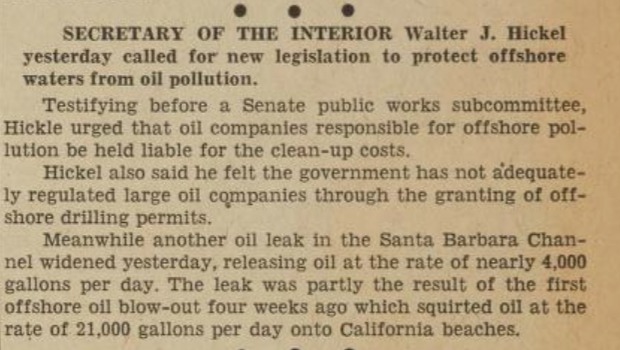

The Santa Barbara oil spill also had an immediate impact in national politics. Interior Secretary Walter Hickel informed Congress that oil companies should have to pay for the costs of the clean-up and admitted that his agency had been too lax in granting drilling permits in the past. Richard Nixon visited the area and promised that his administration would create stricter regulations on oil drilling in coastal waters in response to what he called the "Santa Barbara tragedy." The president also established a panel of scientists and engineers to advise the federal government on the coastal clean-up operation. Nixon, however, embraced resource conservation management and not ecological preservation, telling Americans that "the obligation to develop our natural resources carries with it the duty to protect our human resources. This country can no longer afford to squander valuable time before developing answers to pollution and oil slicks from wells, tankers, or any other source."

Many Californians and other Americans, instead, concluded that public policy should ban oil drilling platforms near highly populated coastal areas altogether. Under pressure, the Nixon administration proposed to cancel all oil drilling permits off the immediate coast of Santa Barbara and designate the waters a marine sancturary. Democratic politicians in California denounced the administration's actions as "too little, too late." Environmentalists also opposed the administration's plan to compensate oil companies for any financial losses caused by the creation of the sancturary. Get Oil Out, a citizen activist group based in Santa Barbara, criticized the president because an oil spill beyond the boundaries of the sanctuary would be just as damaging. One hundred thousand people signed the Get Oil Out petition for a complete ban on offshore oil production, and in response California officials went further than the federal government by halting all drilling in state waters. Under pressure, federal agencies placed an effective moratorium on offshore drilling in California as well. Environmental Action, the organization planning the first Earth Day, expressed the consensus view that the "nation's worst oil spill" near Santa Barbara had "helped spur nationwide concern with the environment."

The Cuyahoga River fire in June 1969 also resulted from industrial oil pollution in an American waterway and raised concerns about the fate of the Great Lakes in general. The Cuyahoga runs through the center of Cleveland, Ohio, and had long been a dumping ground for waste and sewage from the industrial development along its banks. The river had caught on fire more than a dozen times during the past century, but the 1969 incident drew massive national attention even though the damage was minimal compared to previous occurrences. Time magazine ran a cover story highlighting the Cuyahoga River as the national symbol of the transformation of urban rivers across America into "sewers"--the once great but now filthy Mississippi River, the stinking Potomac in Washington, D.C., and a Cleveland waterway with no visible animal life that "oozes rather than flows." Industrial corporations in Cleveland discharged toxic chemicals and waste into the Cuyahoga with barely any regulatory oversight, and the city's antiquated sewer system spilled 25 million gallons of raw sewage daily into the river, and therefore into Lake Erie as well. The Cuyahoga fire brought national attention to the near "death" of Lake Erie, which was receiving 1.5 billion gallons of noxious waste per day from industrial pollution and sewage overflows in Cleveland, Detroit, and other cities. Along with the Santa Barbara oil spill, the Cuyahoga fire and the pollution of Lake Erie and other Great Lakes helped galvanize environmental consciousness, shift public attitudes, and create the climate for federal laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and the Clean Water Act of 1972.

"The Population Bomb"

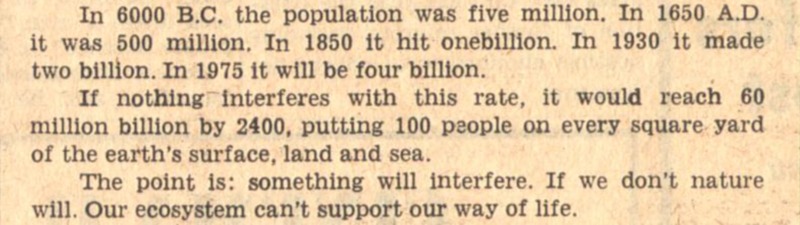

In his controversial 1968 book The Population Bomb, biologist Paul Ehrlich argued the environmental crises of the past decade could be traced to a single cause: overpopulation. It was a simple “numbers game:” the Earth had too many people and too few resources to support them. Ehrlich warned that attempts to stretch the Earth’s resources to support the population would result in mass starvation, epidemics, and, ultimately, the breakdown of social order. He saw population control as the only solution to the problem because “the birth rate must be brought into balance with the death rate or mankind will breed itself into oblivion.” Given the severity of this threat, he argued the US government should incentivize having fewer children and improve access to birth control and abortion. He recommended that the US also encourage population control in developing countries, where birth rates were highest, by making population control measures a condition of foreign aid.

Ehrlich’s ominous message caught the public’s attention and placed the issue on the national agenda. On July 18, 1969, President Nixon addressed Congress in a special message about population growth, which he called “one of the most serious challenges to human destiny in the last third of this century.” He highlighted population growth's impact in the US and abroad, and asked Congress to create the Commission on Population Growth and the American Future to study the issue and discuss how the country would house, educate, employ, transport, and protect “the next hundred million Americans” who would be born in the next fifty years. Nixon warned that "the ecological system upon which we now depend may seriously deteriorate if our efforts to conserve and enhance the environment do not match the growth of the population."

Though the problem began to be studied at the federal level, most of the action on the issue took place in communities and on college campuses. Thousands of college students read The Population Bomb and decided to participate in Earth Day and join the environmental movement. Several leaders of Environmental Action, the group which would coordinate the first Earth Day, credit Ehrlich’s book for motivating them to action. In this “Pledge of Social Responsibility” printed in the Michigan Daily, U-M’s chapter of Zero Population Growth, a movement that sought to bring the population growth rate to zero, asked students to pledge to have two or fewer children “in recognition of the modern crisis of uncontrolled population growth.” As the urgency of the pledge suggests, The Population Bomb helped generate the energy that propelled the country toward Earth Day.

Sources:

DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972-1977, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542493

New York Times, November 21, 23, 1953

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

Environmental Protection Agency, “Two ‘Killer’ Smogs the Headlines Missed,” EPA Journal 12:10 (December 1986)

Sarah Gardner, “LA Smog: the Battle against Air Pollution” Marketplace, July 14, 2014, https://www.marketplace.org/2014/07/14/sustainability/we-used-be-china/la-smog-battle-against-air-pollution

Los Angeles Times, January 22, February 26-27, December 31, 1968, Spetember 19, December 21, 1969

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, "45 Years after the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, Looking at a Historic Disaster Through Technology," January 28, 2014, https://response.restoration.noaa.gov/about/media/45-years-after-santa-barbara-oil-spill-looking-historic-disaster-through-technology.html

Keith C. Clarke and Jeffrey J. Hemphill, "The Santa Barbara Oil Spill, A Retrospective," Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers (2002), 157-162, https://www.scribd.com/document/34113674/1969-Santa-Barbara-Oil-Spill

"America's Sewage System and the Price of Optimism," Time (August 1, 1969)

Ohio History Central, "Cuyahoga River Fire," http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Cuyahoga_River_Fire

Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Paul Ehrlich, The Population Bomb (New York: Ballantine Books Inc., 1968)

Public Papers of the Presidents 1969