Campus Radicalism, Vietnam, and Ecology

In late 1969, the New York Times ran a feature article on campus protests headlined "Environment May Eclipse Vietnam as College Issue." The article covered the build-up to the nationwide environmental teach-in--not yet labeled Earth Day--scheduled for April 22, 1970. According to the Times, "rising concern about the 'environmental crisis' is sweeping the nation's campuses with an intensity that may be on its way to eclipsing student discontent over the war in Vietnam." Student activists on many university campuses had started ecology organizations and environmental awareness groups to protest pollution of the air, land, and water. Many of these ecology activists came from academic programs in natural resources and the sciences and became politically active around issues such as the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, campaigns to preserve wilderness areas, and the movement to ban toxic pesticides such as DDT. But others became more environmentally conscious through their participation in New Left campus demonstrations against the Vietnam War, especially the protests against "ecocide" by Dow Chemical for the manufacture of the herbicide napalm that the U.S. military used to bomb its enemies and defoliate jungles in Southeast Asia. In March 1970 at U-M, the antiwar group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) orgnanized this anti-Dow protest with support from the recently formed Environmental Action for Survival, just a few weeks before the latter group held its major teach-in on the environmental crisis.

The Antiwar Movement and Campus Activism

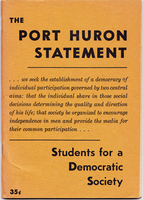

The University of Michigan played a central role in the anti-Vietnam War movement during the 1960s and early 1970s. Many of the key activists in Students for a Democratic Society, the leading campus antiwar organization, were students at U-M, including Tom Hayden, the primary author of the Port Huron Statement of 1962. This influential document argued that college students in the New Left should use the campus as a base to transform American society and politics: "We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit." The Port Huron Statement, athough not usually viewed as part of the environmental movement, criticized "uncontrolled exploitation . . . of the earth's physical resources" on the first page. The SDS vision of "participatory democracy," and attacks on the runaway power of corporations and government, would soon echo among environmental activists on campus as well. Ecological principles also resonated with the Port Huron Statement's call for greater citizen influence over the economy, as "major resources and means of production should be open to democratic participation and subject to democratic social regulation."

Faculty at the University of Michigan organized the first teach-in on the Vietnam War in March 1965, establishing a template that campus activists would employ to generate awareness and mobilize political action on many other issues, including the environmental teach-ins of spring 1970. The Faculty Committee to Stop the War in Vietnam set events in motion and invited experts from across the nation to speak at an all-night event on March 24-25, with around 3,000 students attending various sessions. Anthropology Professor Eric Wolf, in this news footage, labeled the teach-in a success in bringing pressure to bear on U.S. policy, because "they're not telling us what is going on and people have a right to know and we have the right to tell the government what we think." The teach-ins spread to more than fifty universities around the country, and the next month SDS led the first major demonstration of the antiwar movement, the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam. Antiwar activism continued at the University of Michigan and other campuses for the rest of the decade, including resistance to the draft and protests against university research that benefited the military-industrial complex.

Linking the Problems of War and the Environment

During the mid-to-late 1960s, the campus protests against Dow Chemical brought the radical antiwar movement into an ecological politics that overlapped with the growing environmental activism among college students more generally. Dow, an industrial chemical company based in Midland, Michigan, had deep ties to scientific researchers at U-M when the campus SDS chapter launched a protest campaign in 1966. The antiwar movement targeted Dow's manufacture of napalm under contract with the U.S. Department of Defense, and also its Agent Orange defoliant, as weapons of "chemical warfare" that violated human rights, caused birth defects, and devastated the natural landscape. Major protests against Dow recruiters occurred on dozens of college campuses, including a pivotal fall 1967 demonstration at the University of Wisconsin, where local police tear-gassed student activists. SDS members at the University of Michigan also held multiple demonstrations against the administration for allowing Dow to recruit students through campus facilities, and they accused the company of the "ecologically disastrous" destruction of one-fifth of the Vietnamese countryside. This flyer challenged Dow Chemical's position that supporting the American war effort was "good citizenship" and revealed an emerging alliance between U-M antiwar activists and the new group ENACT, which co-sponsored the protest as part of its movement to build environmental awareness on campus.

The gallery above provides a sampling of the intersection of ecological awareness and confrontational antiwar politics at the University of Michigan during the first months of 1970 in the lead-up to the ENACT Teach-In scheduled for late March. On January 21, members of SDS 'attacked' military recruiters on campus and also disrupted a job recruitment event behind held in the Chemistry Building for Allied Chemical, a manufacturer of the pesticide DDT. The radical activists dumped dead fish and a bird in the room, and sprayed it down with pesticides in order to demonstrate the poisionous toxicity of DDT for humans and animals. While ENACT's steering committee agreed to co-sign the SDS leaflets against Dow, the environmental group declined to endorse the direct-action protests designed to shut down the recruiters and specified that it did not support any illegal activities--a sign of tensions between ecological activists and antiwar radicals that would mark the teach-in as well.

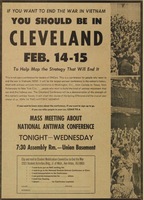

The Michigan Daily edition that covered the SDS guerilla protest also contained an advertisement by ENACT inviting U-M students to participate in the planning for the environmental teach-in. In February, the Daily included an advertisement by an Ann Arbor antiwar organization recruiting students to attend a national conference in Cleveland to mobilize against the Vietnam War. In early March, anti-Dow protesters marched with signs meant to convey the chemical properties of napalm along with "Babies Burn, Dow Gets Rich" messages. At the same time, the new Radical College at U-M organized a forum where officials from Dow Chemical boasted of their innovative pollution control technologies and denied the charges of a professor that the company's production of napalm and other herbicides constituted "crimes against humanity." Student radicals held up signs attacking Dow througout the event.

George Coling, a member of the planning committee for the ENACT Teach-In, explained the ecology agenda as "say yes to the environment, no to the war." Coling had participated in antiwar protests as an undergraduate at the University of Rochester before he arrived at U-M in the fall of 1969 as a graduate student in public health. He had a 1-A classification (eligible for the military draft) and a one-year deferrment, and the fear of being sent to Vietnam shadowed his experiences in Ann Arbor. Several ENACT leaders were being "hounded by our draft boards," Coling recalled in 2017, and so "the actual work of organizing of the Teach-In was a counterpoint to the insanity of the war." Coling and his friend Bill Painter sought conscientious objector status and viewed environmental activism as a way to make a positive contribution to social and political change during a time when violence seemed everywhere, from urban racial unrest to the National Guard killings of four protesters at Kent State to the unceasing U.S. bombing campaign in Southeast Asia. Soon after the Teach-In, Coling moved to Washington and worked with environmental groups pressuring Congress to ban the toxic defoliant Agent Orange. In this interview segment, Coling recounts living with the "magnitude of the stress and the craziness" of the Vietnam draft and how working with ENACT meant instead "doing something positive for the environment."

Prominent scientists and other ecological advocates increasingly emphasized the connections between the environmental crisis and the Vietnam War as Earth Day approached. In early 1970, a Time Magazine cover story designated biologist Barry Commoner, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, the "Paul Revere of ecology." Commoner, who would give the keynote address at the ENACT Teach-In at U-M, repeatedly warned national audiences of the "links between the environmental crisis, the evils of war in general, and the war in Vietnam in particular." He argued that the fallout from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and radioactive fallout from subseqent nuclear tests illuminated how the American war program represented a "vast technological blunder." But Commoner labeled the military's use of napalm and other herbicides in Vietnam the worst disaster yet, and he accused the Pentagon of misleading scientists and the public about the environmental devastation of forests and food crops from their deployment in the war. With strong language, Commoner labeled the conflict in Vietnam "the first ecological warfare conducted by the United States since the attacks on American Indians."

Environmental Action, the group that coordinated the national Earth Day events on April 22, 1970, also highlighted the links between the ecological crisis and the Vietnam War. In March 1971, the Environmental Action newsletter published an environmental expose of "Vietnam: The True Costs of War." Since 1962, American military planes had sprayed roughly 20 million gallons of herbicides in Vietnam. Frequent napalm strikes decimated forests in a matter of minutes, part of a defoliation campaign that had destroyed millions of acres of forest land and food crops. Five hundred pound bombs dropped from B-52’s had left craters 45 feet wide and 30 feet deep, providing a breeding ground for disease-riddled mosquitos. The U.S. military's defoliation campaign, in a bitter twist on the famous Smokey the Bear catchphrase, should be known as "Only you can prevent a forest." Environmental Action also questioned whether the Nixon administration was keeping its December 1970 promise, made under pressure from environmental and antiwar groups, to phase out herbicides in Vietnam. But regardless, the effects of the defoliation campaign had been devastating in terms of human suffering and ecological balance in Vietnam, including terrible losses for plant and animal life. Environmental Action endorsed antiwar demonstrations because "war is the worst pollutant" and offered the somber conclusion that "the ecology of Vietnam will never recover from the United States' presence."

Sources for this page

Gladwin Hill, “Environment May Eclipse Vietnam as College Issue,” New York Times, November 30, 1969, pp. 1, 57.

University of Michigan Television Center, "Vietnam Teach-In, 1965," Box 2, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

"Resistance and Revolution: The Anti-Vietnam War Movement at the University of Michigan," http://michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/antivietnamwar/

Students for a Democratic Society, The Port Huron Statement (1962), http://www.sds-1960s.org/documents.htm

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

Jay Cassidy Collection, Michigan Daily Alumni Photographers Collection, Bentley Image Bank, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

University of Wisconsin, "A Turning Point: Six Stories from the Dow Chemical Protests on Campus," https://1967.wisc.edu

Dylan Lettinga, "The Dow Chemical Company--Midland, MI," October 11, 2015, Military History of the Upper Great Lakes Region, http://ss.sites.mtu.edu/mhugl/2015/10/11/the-dow-chemical-company-midland-mi/

Barry Commoner, "Beyond the Teach-In," Saturday Review (April 4, 1970)

Barry Commoner, "Keynote Address: Teach-In on the Environment," March 11, 1970, Environment: ENACT Conference 1970, Vertical File Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

George Coling to Matt Lassiter (E-mail communication), December 2, 2017

Interview of George Coling by Amanda Hampton and Matt Lassiter, December 7, 2017

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), 3-4, 20-24, 37-46

James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994)