ENACT Teach-In: Making History

It has been nearly 50 years since the Environmental Teach-In, and although time has passed, those who planned and worked on the Teach-In remain. Reflecting on their experiences, members of ENACT we interviewed recall if they thought they were part of history at the time of the Teach-In. Answers varied from person to person, but each person felt at the time of the Teach-In what they were doing was right, regardless if it was historical or not.

David Allan, the co-chair of ENACT, first reflected on the Teach-In and it's success weeks after the program ended and the national program had come and gone as well. At the time, Allan considered the Teach-In a success because thousands of people became aware of the issues including issues in the human and natural environment. The public's newfound understanding of ecology was a sign of success to Allan, however, change in the environment was not something he expected from the Teach-In. Although people were changed individually, Allan stated Teach-In did not cause a major change and change over time might be so slow it would be almost unnoticeable.

Allan's critical analysis of the Teach-In remained the same almost 50 years later when he was asked if he felt like part of history while planning the Teach-In and running ENACT. His answer: "I certainly didn't think of it that way." To Allan, the Teach-In was an idea that developed organically into something wonderful, but was not historical. He stated "my looking back on it, it all went wonderfully," indicating that to him, the Teach-In is nothing more than a pleasant memory and a showcase of what can happen when ideas grow.

Doug Scott, the co-chair of ENACT, when asked if he felt like he was a part of history, recalled a story from the day after the Teach-In. He and another member of ENACT were in the ENACT office clearing it out when Luther Carter, a reporter from Science Magazine, strolled into the office. Upon entering, he told Scott and the other member, "you know you guys are never going to do anything this big in your life again." Carter's comment caused Scott to pause and think about his accomplishments at the Teach-In and all Scott could think was "my god, what happened here?" Although Carter's comment ended up not to be true, as Scott went on to save vasts amounts of the Alaskan wilderness as well as other natural habitats through his political work, Carter's comment affected Scott at the time.

Scott's sudden realization of the size and scope of the Teach-In shows that while planning the Teach-In and even during the Teach-In itself, Scott did not see it as historical. He was simply a student with a passion for the environment and politics and wanted to educate the public on the environmental issues of the day. It was only after the event did it hit him how huge and important his work and the Teach-In were. This speaks to the mission of ENACT and the former members of the organization. ENACT's Teach-In was not made to be a historical event, it was made to educate a population in hopes to better the future for everyone. ENACT wanted the acts taken after the Teach-In to be historical, like ending pollution, controlling the population, and saving the Earth.

Elizabeth, a member of ENACT, did not believe she was a part of history during the planning and execution of the Teach-In. In her eyes, ENACT was "not a part of history, [they] were just doing what [they] were doing." Nearly 50 years after the Teach-In, she recalled the larger environmental movement did not happen until after the Teach-In, so she never considered the Teach-In historical. To Grant, Enact was "doing the job [they] needed to do at Michigan and it grew from there." Instead of history, the purpose of the Teach-In was to educate people on the important piece the environment played in the abundance of problems prevalent in the 70s. The Teach-In showed people that although they could not end the War in Vietnam or racism in a day, they could become involved in their communities and participate in small daily actions to improve the environment. Grant believed ENACT's mission was to promote democracy and encourage people to get involved, not to make history books.

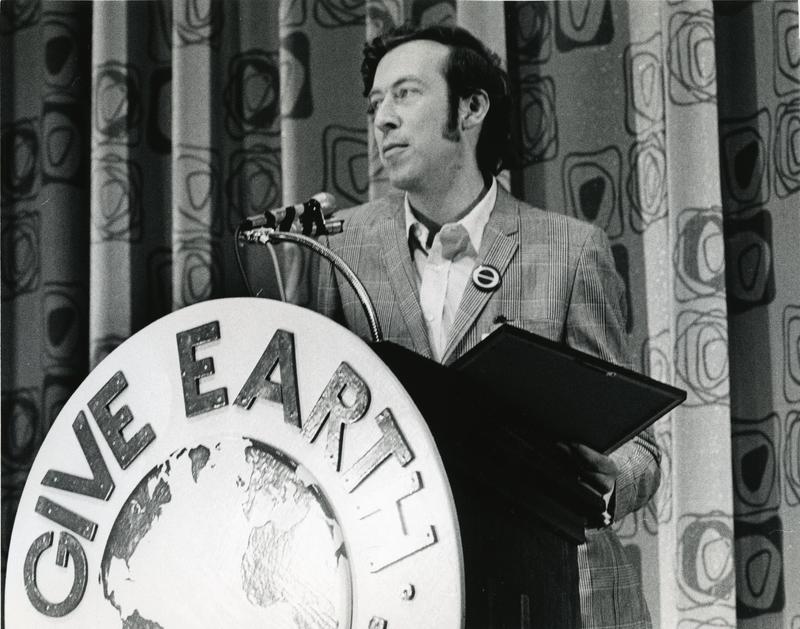

Unlike his colleges in ENACT, George Coling believed he was a part of history during the Teach-In while serving on the Steering Committee. The moment that most stood out to Coling was during a Teach-In event at the Chrysler. Less than 30 feet away from him stood Edmund Muskie, the presidential nominee in the previous election. Being this close to a political figure caused Coling to realize the large impact of the Teach-In and the historical nature of it. This encounter was so profound for Coling that after the Teach-In he held onto materials for future historical use and pursued a career in the environment. Although Coling found the Teach-In historical, he thought ENACT could have done more community outreach, especially with Detroit and other neighboring cities.

Despite their different memories and interpretations of the Teach-In, each member of ENACT played an integral part in educating a population on the environment and how they could get involved to improve the planet. Although members of ENACT saw the Teach-In as both history in the making and another day in their lives, the University of Michigan students researching the Teach-In nearly 50 years after the event see it as a moment in history. ENACT's actions, mission, and hopes for the future resonate today and have deeply impacted each and everyone involved with this research project. We have been inspired to do more and follow our passions to do good in the world. We hope through this project, we have done ENACT justice, and show that students can change the world.

Sources

University of Michigan Television Center, “Enact: Teach-In on the Environment,” 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Interview of David Allan by Amanda Hampton, November 6, 2017, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Interview of Doug Scott by Amanda Hampton and Meghan Clark, November 17, 2017, by remote videorecording

Interview of Elizabeth Grant Kingwill by Maya Littlefield, November 20, 2017, by remote videorecording

Interview of George Coling by Amanda Hampton and Matt Lassiter, December 7, 2017, by remote videorecording