Toxic Chemicals and Citizen Activism

The series "Ecology: Man in the Environment" produced by U-M and the School of Natural Resources (SNR) in 1970 put scientists, politicians, U-M students, and concerned citizens in conversation with one another to inform the public on environmental issues. In this episode "Who Governs Nature?," Professor Justin Leonard from the SNR posed the question of how individual citizens could become involved in governmental decisions on how best to defend the environment. Out of the environmental movement emerged a new role for citizens in environmental politics. "Scientists, ordinary citizens, schools, universities, conservation organizations, citizen groups, like the garden clubs, the League of Women voters," Michigan Representative John Dingell stated in 1970, "are all now working to make this system work" by banning together to increase public pressure on their local, state, and federal governments. Citizen participation, according to Tony Abar, a Maryland Department of Natural Resources official, "can become effective when he picks out a specific issue..., organizes, develops his information base, becomes familiar with the people who play important decision-making roles, and then organizes to effectively have an influence on policy." This was the methodology adopted by many grassroots organizations in the 1960s and 1970s to address environmental concerns, including toxic chemicals.

Silent Spring and Women's Activism

In 1962, The New Yorker published Silent Spring, a chilling account by scientist Rachel Carson that exposed the dangers imposed on the environment by the ubiquitous usage of pesticides. According to Carson, although pesticides proved remarkably effective at their intended job, they also unintentionally damaged other parts of the environment, such as soil and birds. Her scientific-based claims frightened people across the country and led to a widespread upheaval of the widespread American understanding of technology as an innocuous remedy to daily ails and a new environmental consciousness. In this episode of "Ecology: Man and the Environment," the narrator refers to Silent Spring as "one of those books that changed the world."

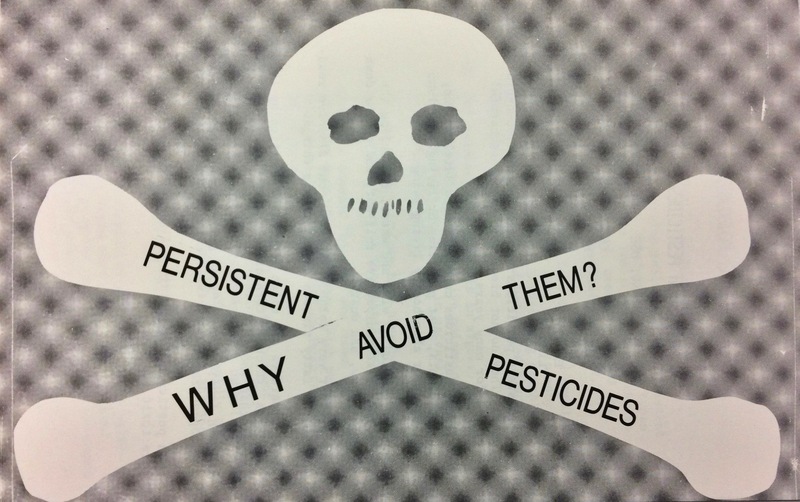

Silent Spring shifted the "private, scientific debate" to "a public, political issue," inspiring women's organizations and other local groups to act. Many existing organizations, such as the League of Women Voters and the Garden Club of America, shifted their political gaze towards pesticides. The book propelled other environmentalists, especially women, to action, forming grassroots organizations in their communities, lobbying politicians, and producing educational pamphlets about the hazards of pesticides, such as this document created by the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC), which Joan Wolfe, an environmentalist in Grand Rapids, founded in 1968. Environmentalists continued to advocate for and track the progress of the toxic chemical campaigns, and Environmental Action, the newsletter published by the group that coordinated the national Earth Day in 1970, frequently covered the issue.

One such pesticide under attack was DDT, which had become widely regarded as a heroic scientific intervention when it effectively killed insects and harbored diseases, such as typhus and malaria, during World War II. Over the next decade, the pesticide came into more popular use for fending off prevelant nuisances, such as insects, weeds, and rats, from food crops. In other words, DDT threatened the health of not only the sprayers themselves but also any individuals who consumed the produce. Unfortunately, the most effective pesticides also proved "more likely...to cause significant damage to non-target organisms and to the environment." Silent Spring brought these scientifically grounded arguments about "man's war against nature" to the public in comprehensible language for the first time and thus demonstrated the acknowledgment that exacting environmental change would require the combined efforts of scientists and activists.

The Politics of Pesticides

Carson's conclusions received intense scrutiny from scientists and politicians who reinforced the undeniably positive aspects of pesticides. In Kennedy's Science Advisory Committee's 1963 report "Use of Pesticides," the authors sought to lessen the sense of horror instilled by Silent Spring, pivoting on the tension between risks and gains inherent in narratives of "progress." The report reminded readers of the positive effects of DDT, such as "how remarkably effective the modern organic chemicals are" for insect control and food production. On the other hand, the review also acknowledged the hazards imposed by pesticides, stating "while they destroy harmful insects and plants, pesticides may also be toxic to beneficial plants and animals, including man." Although the report claimed science had not conclusively proven the extent to which DDT ingestion threatened human health, it did estimate 150 deaths per year from chemical exposure, which was probably low because the estimate did not account for longer term repercussions, such as cancers. The Committee recommended the implementation of stronger regulations and continued scientific research on these chemicals as part of a "comprehensive program for controlling environment pollution." Further, the Committee proclaimed the "elimination of the use of persistent toxic pesticides" as their "goal," but what form this regulation would take remained to be seen.

One month after the publication of that report, Rachel Carson testified in a Congressional hearing on the subject of "environmental hazards" in an effort to unveil the "many forces" which people still considered "mysterious." Senator Ribicoff welcomed Carson, acclaiming her as "the lady who started all this." "All people in this country and around the world," he declared, "owe you a debt of gratitude for your writings and for your actions toward making the atmosphere and the environment safe for habitation, not only by human beings but for animals and nature itself." Although many politicians and scientists sought to undermine her claims, Carson had undeniably suceeded in making scientists, politicians, and ordinary citizens take a step back and examine the impact of the modern way of life on the environment. In her opening remarks, Carson contextualized the issue of hazardous pesticides as a fraction of a larger whole of problems posed by man's technological ventures to control nature.

"When we review the history of mankind in relation to the earth we cannot help feeling somewhat discouraged, for that history is for the most part that of the blind or short-sighted despoiling of the soil, forests, waters, and all the rest of the earth's resources. We have acquired technical skills on a scale undreamed of even a generation ago. We can do dramatic things and we can do them quickly; by the time damaging side effects are apparent it is often too late, or impossible to reverse our actions. These are unpleasant facts, but they have given rise to the disturbing situations that this committee has now undertaken to examine." - Rachel Carson

On Trial: DDT

Ultimately, the use of hazardous pesticides persisted unregulated by the federal government and thus concerned citizens had to take another route to eliminate DDT: litigation. In 1966, a small group of scientists and a lawyer on Long Island won a lawsuit against a local mosquito control commission over their abusive use of DDT. In 1967, that group of scientists, inspired by their legal victory, incorporated as Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) with the objective of protecting the environment through legal action. Only one week later, the EDF moved the battle to Michigan, filing two suits regarding the spraying of dieldrin and DDT on elm trees, which threatened songbirds and other wildlife.

As U-M Law Student Roger Conner and U-M Lecturer Dr. James Swan describe in "The Environmental Lawyer," whether the plaintiffs won or lost, the court publicity raised awareness and inspired extensive public education and activism across the state. Through a series of litigation and citizen action, Michigan became the first state to ban the sale of DDT in 1969.

Encouraged by the banning of DDT in three states, the EDF decided to take on the federal government. With the support of the West Michigan Environmental Action Council, the National Audobon Society, and the Sierra Club, they filed a legal petition against the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) under whose jurisdiction pesticide control fell. When the USDA ignored their petition, EDF took the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals. When the Court requested their response, the USDA denied the allegations of the petition. Once again, EDF presented the case to the appellate court and once again the USDA denied their claims. In response, EDF took the case to the Court a third time, and the Court sided with EDF. In the same year, the federal government established the Environmental Protection Agency, and pesticide regulation shifted to them. Ultimately, after a series of studies, hearings, and court decisions, the EPA banned DDT nationally in 1972.

Lead Poisoning

Although it received less national attention than pesticides, lead poisoning was another key issue in the 1960s, especially in inner-city communities. Many activists, especially African American activists, mobilized around combatting and preventing the dangers of lead poisoning. These urban campaigns intersected with the civil rights movement and contributed to growing consciousness about how environmental hazards disproportionately affected poor, working-class, and nonwhite communities— an awareness that later became known as environmental justice.

Environmental Action also covered this issue in the newsletter article "Lead Poisons Ghetto Children." Although legislation outlawing lead paint passed in the 1950s, the hazardous paint still coated the walls of homes across the country, especially in inner-city communities. As a result, each year over 112,000 children suffered symptoms of lead poisoning, such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and depression. When ingested consistently over time, lead poisoning could lead to severe brain damage or, in some cases, even death. Lead poisoning could be treated with adequate medical attention, but children in the inner city often had "grossly inadequate" access to medical treatment. Therefore, prevention would require "action programs on the part of the community and city agencies, and landlords, to de-lead housing." In St. Louis, for instance, activists protested, provided blood tests for children, and pushed local officials to act on the issue in the northside ghettos throughout the 1960s and 1970s. They also reached out to scientist Barry Commoner who helped them found the Environmental Field Program. Eventually, the local government passed a lead law, but the law and its subsequent reiterations failed to thwart lead poisoning.

During Barry Commoner's keynote address at the U-M Teach-in in 1970, he referenced lead poisoning as an example of the ways in which environmental issues affected poor people disproportionately. Environmentalists considered the protection of the environment to be a universal responsibility, but many also acknowledged that some groups had more at stake when we failed to do so. Therefore, Commoner asserted that the environmental movement need not come at the expense of other social movements but rather as an extension of them.

"A white suburbanite can escape from the city's dirt, smog, carbon monoxide, lead, and noise when he goes home; the ghetto-dweller not only works in a polluted environment, he lives in it. And in the ghetto he confronts his own, added environmental problems: rats and other vermin, the danger of lead poisoning when children eat bits of ancient, peeling paint. And, through its history, the black community can be a powerful ally in the fight against the environmental crisis." - Barry Commoner

Sources for this Page

West Michigan Environmental Action Council, Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

U-M School of Natural Resources, "Ecology: Man and the Environment," Part 12: "Public Pressure," 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Records, 1948-1987, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

University of Michigan Television Center, “The Environmental Lawyer,” 1970, Box 8, Media Resources Center (University of Michigan) Films and Videotapes, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Michigan Daily Digital Archives

Rachel Carson, "Silent Spring," The New Yorker, June 16, 1962, pgs. 35-99.

Thomas Dunlap, DDT: Scientists, Citizens, and Public Policy (Princeton: Princeton Legacy Library, 2014), 97.

Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013) pgs. 23-33.

Chad Montrie, The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), 1-21

Environmental Action, Earth Tool Kit: A Field Manual for Citizen Activists (Pocket Books, 1971), 195-210

Environmental Action Newsletters

Charles F. Wurster, The Decision to Ban DDT: A Case Study (National Academy of Sciences, 1975), 8-9