Nike Negotiations Break Down

Nike Negotiates

From the start of the anti-sweatshop movement on campus, Nike has been in contact with university administration to make the requirements on suppliers workable for their business. As a major multinational corporation, Nike played a leading role in the Apparel Investment Partnership (AIP), which adopted a set of policies that eventually became the foundation for the FLA. Nike was instrumental in stopping the AIP from adapting a living wage provision or the public disclosure of their factories, as it believed these policies would hurt its business in the future.

On March 10, 1999, Phil Knight sent a letter to President Bollinger on Nike joining the FLA, saying, “While I believe the FLA’s provisions are sufficient and (from a business competitiveness point of point of view) more reasonable, Nike doesn’t believe this should be a stumbling block for an institution to join the FLA. Consequently… Nike is prepared to provide to these institutions the names, addresses, and locations of manufacturing facilities.“ Nike did make an effort to disclose the location of their factories to university administrators, as long as that information was not made public. However, SOLE had repeatdly argued that it would be impossible for the public to make Nike accountable for their labor abuses if everything was done behind closed doors.

Nike did more to head off criticism and improve the working conditions in their contracting factories. Nike joined the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities, a project dedicated to making management more responsive to the concerns of workers. Nike also increased the minimum wage for workers in their Indonesian factories several times in 1999, and added benefits like healthcare and transportation stipends. Still, these improvements did little to mollify the national and campus anti-sweatshop movement, and their concern over Nike’s business practices continued.

Nike and Michigan Part Ways

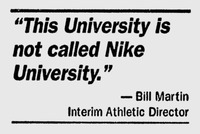

Nike steadfastly refused to deal with universities that had joined with the Workers Rights Consortium (WRC). However, when SOLE protestors and President Bollinger agreed to end the sit-in of LS&A Dean Newnan’s office on February 18, 2000, by joining the WRC, it seemed as though the university and its supplier were destined for a showdown. Michigan firmly maintained that any agreement would require greater monitoring of Nike factories for them to continue supplying the university’s apparel, along with better wages for workers.

Still, both parties had some reason to hope for a compromise. Negotiatations were already underway for a multi-year extension on their contract. This partnership was still one of the most lucrative in all of college sports, and Nike would be forgoing millions of dollars in advertising revenue if they lost their contract. And many students on campus were clamoring for an extention. While anti-sweatshop actiivsts on campus had opposed NIKE for years, many of the athletes prefered Nike products to other major sports apparel makers.

On April 28, 2000, Nike accounced that it was severing its ties with the University of Michigan, along with Brown University and the University of Oregon, three schools that had recently joined the WRC in response to student protests. In explanation, Nike director of college sports marketing released a statement saying, "They made the requirement that they could impose standards at any point during the contract and we'd have to adhere to them... I don't forsee [getting back with Michgain]." Nike officials rejected the claims that they used substandard labor practices in manufacturing their apparel, and they continued to emphasize their positive role in developing low-income countries.

However, many students and members of the community cheered Former student athlete Dhani Jones said, “Every kid from five to 85 loves Nike. They think of Nike, they sleep with Nike and they dream of Nike. (But) any time an institution like Michigan puts its name on the line, that’s a tremendous thing,”

Kukdong Factory Strike

Despite Nike's years of work to shed its sweatshop image, some manufacturers in the company’s production chain continued to use low wage labor and offered few meaningful protections for workers. Nike once again became the focus of the college anti-sweatshop movement when a group of workers decided to strike at one of their manufacturer's plants, the Kukdong apparel factory in Atlixco, Mexico in 2000.

It was hardly a national news story when a garment manufacturer did not pay their workers with a living wage or did not provide them the same standards as their western counterparts. However, the Kukdong strike shocked the world because the factory’s management violated any number of local, national, and international labor right laws, all while being “regulated and monitored” under the auspices of the FLA. The Kukdong factory began manufacturing Nike products in March 2000, which included the apparel of the University of Michigan and other colleges from across the county, which meant that it should be regulated by the FLA and the CLC’s code of conduct.

Workers alleged that management the more notable abuses by management. They claimed that the food served in the company cafeteria was infested with maggots, that they did not receive the legally mandated minimum wage or their Christmas bonuses, and that they were not permitted bathroom breaks. Several women also accused the company of condoning sexual harassment by supervisors towards low level employees. A PriceWaterhouseCoopers monitor visited the factory on March 6, 2000 and documented a number of legal violations and violations of FLA guidelines. Nike was made aware of the results of this investigation, yet the company did not choose to take action or end their contract with Kukdong.

On December 15, 2000, the Kukdong workers decided they had suffered enough, and they began a boycott of the company cafeteria. Despite a rash of firings and demonstrations by employees, the workers continued their defiance of factory management, and this culminated with a massive labor strike on January 9, 2001. Police were brought in to end the demonstrations, and the government-run union pressured workers to go back to Kukdong.

When a claim against the Kukdong factory was filed with the WRC, the story of the factory strike became national news, and it launched a number of calls to action from anti-sweatshop activists. The national United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) organization put together a list of demands on the Kukdong factory, including the reinstatement of striking workers and the right to form an independent union. The WRC launched its own investigation into the strike, but many of its constituent universities began to take action on their own.

At the University of Michigan, SOLE put pressure on the school to leverage its influence as a Nike affiliated university to improve conditions at Kukdong. SOLE member Jackie Bray worked with university administration to write a letter to Nike condemning their practices at Kukdong and demanding that the company to institute stronger workplace protections for manufactures who produce Michigan apparel.

This episode occurred in the midst of new negotiations between the university and Nike to reestablish their apparel contract. While labor abuses were nothing new for collegiate apparel manufacturers, the scale and brazenness of the management’s treatment of workers at the Kukdong plant shocked the world. Moreover, it highlighted the failings of national anti-sweatshop policies. Nike, a founding member of the Apparel Industry Partnership and the Fair Labor Association, still ended up conducting business with an abusive factory despite protections in place to protect the workers of member corporations. Even in the face of this negative publicity, the university seemed set on restoring their contract with Nike, as without it they would continue loosing hundreds of thousands of dollars. However, this episode galvanized students to apply greater pressure on Nike and the university and brought new life to activists on campus.

Citations

Letter from Phil Knight to Lee Bollinger on joining the FLA, President's Office of the University of Michigan, March 10, 1999.

Raphael Goodstein, "End of an Air-A," The Michigan Daily, May 1, 2000.

Anna Clark, "Labor Activists Rally Against Nike Deal," The Michigan Daily, January 18, 2001.

USAS, "Workers Strike at Nike-Related Plant," Newsletter of the Anti-Sweatshop Movement, February 2001.

Hannah LoPatin, "Student's Question Future of Nike, University Partnerships," The Michigan Daily, May 1, 2000.

Boyne, David, Grace Rosile, and J. Carillo, "The Kuk Dong Story: When the Foxes Guards the Hen House," (New Mexico State University: June 1, 2015), http://business.nmsu.edu/~dboje/AA/kuk_dong_story.htm.